NY Arts: What is your artistic background? Do you identify as a filmmaker or as a painter?

Russell Sheaffer: I’ve been working on films for a while now — editing and producing for others and directing my own experimental work. I like to think of the experimental work that I’m doing as (often abstract) moving images grounded in the world of theory. I received my B.A. in Film and Media Studies from UC Irvine, my M.A. in Cinema Studies from NYU, and am currently working on Ph.D. at Indiana University in the Department of Communication and Culture. I’ve been really fortunate in that all of the university departments that I’ve been a part of have been very theory-heavy critical studies programs that often allow their students the space to make visual art in response to the theoretical work that they are grappling with. That amalgamation of film theory with media making has been and remains really vital to how I conceptualize my own work.

NYA: Is Acetate Diary an independent work in your oeuvre, or have you worked in this style previously?

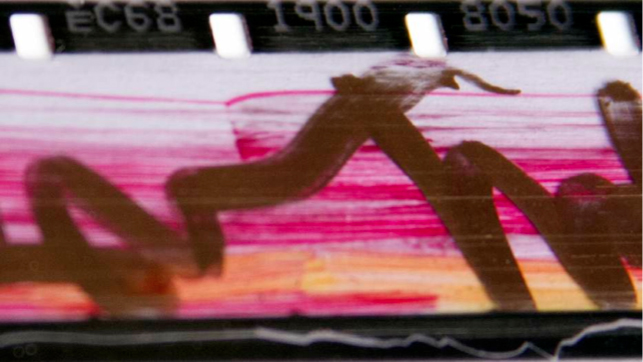

RS:Working with film (and here I mean film and not video) has been really important to me and it’s something I’ve been really focused on since my time at NYU. I’m interested in the ways that we can use film that are different from the ways that we can use digital video. What sorts of images, light patterns, or paintings can we create on acetate film and how do they differ from those we can make digitally? I keep hearing that “digital has replaced film” and I think—in large part—”OK, fine.” But what that way of thinking forecloses is all the kinds of art making that actually rely on the medium—that rely on the acetate. To that extent, Acetate Diary is one of pieces that I’ve made that try to push back on the medium. On a practical, stylistic level, though, it’s the first piece that has relied wholly on the process of scratching and painting—I’ve used those techniques before, but usually in tandem with other processes as well.

NYA: What about the accident made you want to express the idea of a diary on film in this way?

RS: After the accident, I gradually started feeling a little bit better and thought to myself “OK, I’m getting better; eventually I will feel like myself again.” Then, last summer, my body started aching in ways it hadn’t been before. I saw a doctor who told me that, essentially, my jaw joint had completely displaced its cartilage and was in the process of wearing itself down. I was really crushed in a lot of capacities—all of a sudden, it didn’t seem like there was this trajectory that lead from accident to feeling better—at least for the immediate future it was going to be a cycle, not a straight line. When I was a kid, my mother used to give me newspaper when I was frustrated and told me to rip it up—to let out whatever aggression and emotion was inside—and that’s what I wanted to do with Acetate Diary. I wanted to give myself total freedom to simultaneously create and destroy, to beat the hell out of that roll of film, to create something completely instinctual. By using the roll of film as a literal diary—with words, drawings, scratches, and thumbprints—I wanted to capture the urgency of the completely conflicting emotions that I was feeling at a very specific moment.

NYA: How do you see this operating as a diary, assuming the content of the film is strictly visual and avoids using words?

RS: The film actually incorporates both. When I say “diary” I don’t mean to just limit it to words—I also think of the drawings and doodles that folks keep in their diaries as parts of the “diary,” too. But there are words that run pass the projector’s bulb—for the most part, the diary is written from left to right on the 100 feet of film, which means that when you watch it your brain understands those words less as words and more as abstract patterns. The sound that you hear, too, is all a series of words and drawings that I etched into the optical audio track of the 16mm film. As I was painting and scratching the film, I loved the idea that, through this process, I could attempt to take these abstract emotion that I was feeling, make them somewhat concrete by writing them on the film, and then re-abstract them by projecting the film. It makes the piece both public and private in a way that I find really fascinating.

NYA: Are you planning on working in this style moving forward?

RS: I love painting and scratching on film—it’s such a wonderful, strange experience. I’ve been experimenting more and more with the technique and have been staging some live performances in which I’ll draw on the film live as it passes through the projector, which allows you to see the color and shape as the paints dry. I’m really excited to keep on experimenting with the possibilities that paint and acetate allow.

NYA: Who do you see as your aesthetic peers? From what or whom do you derive the source of your inspiration?

RS: There are so many incredible artists who have done similar work in the past—perhaps the most obvious being Stan Brakhage and Len Lye—but I’ve been really intellectually inspired by the work of folks like Jennifer Reeves and Jodie Mack, too, who have also been experimenting with how far you can push film—and I mean that in so many ways. I’ve been involved with the Orphan Film Symposium for a while now, too, and having conversations with the incredibly diverse array of archivists and media makers who frequent the symposium is always a pretty inspirational experience.

NYA: Please tell us something about the process of making this film that may not be readily apparent when viewing the work.

RS: One thing that people always seem curious about is the timeframe that the piece encompasses—and it’s very strictly defined for me. The film was made during two weeks in October 2013 (and has not been touched since.) I gave myself total license to work on it non-linearly—I would jump around and paint the end first, then the beginning, then the end again, then the middle, etc.—so you aren’t getting a sense of time that progresses in a simple fashion but, when you watch the film, you are getting a dose of a very temporally specific moment in my life. Also, Acetate Diary is one of a series of works (three so far, all with highly different styles) that grapple with my body and subjectivity post-accident.

NYA: Where can we find more of your work?

RS: Good question! A couple of my films are available at the Filmmaker’s Co-op in New York, but people can always reach out to me directly—we’re now on the hunt for places that are interested in future screenings of Acetate Diary (as well as my other trauma-inspired films) and I’m always really eager to get my work out there for folks to encounter.