Mitchell/Riopelle: Nothing in Moderation

On my way to this exhibition I was thinking of Joan Mitchell and Jean-Paul Riopelle as a Golden Couple of a Golden Age. The Golden Age is true. Paris still had its charm and New York was rising into its future glory. Riopelle was a golden boy, irresistible and charming with his expensive race cars — including Bugattis — boats, properties and artistic success. Mitchell was a very confident person, athletic and not shy about her body at all. Looking at photographs with her lovers we can’t miss seeing the sexual magnetism radiating from her. It was a good match in many ways, but they were everything but a golden couple.

Both Riopelle and Mitchell came from middle-class backgrounds, with Mitchell from Chicago, Riopelle from Montreal. Riopelle exhibited with Les Automatistes in Montreal in 1946 and signed the manifesto Refus global, written by Borduas in August 1948, gathering a group of abstract painters who wanted to break free from the strict Catholicism of Quebecois life. After WWII artists came to Paris longing for a bohemian life and Andre Breton ruled like a pope, surrounded by a large group of painters and writers. Riopelle met him in 1947 but remained independent, never associating himself with any group. His circle of friends in Paris included Sam Francis, Samuel Beckett and many more of the geniuses of that era.

The artists of the first generation of Abstract Expressionism in New York, like Willem Kooning, Hans Hofman, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock and the poet Frank O’Hara among others, created an important movement and a new centre of visual art started to build up around them. The New York art world in the early 1950s was dominated by men but Mitchell, who spoke frankly, aggressively and emphasized that her gender was not important, but being a painter was, established her significance among them.

When Mitchell and Riopelle met in Paris in 1954, he was already a well-known and successful artist, while Mitchell was just exploring Paris on a grant. They remembered differently about the place they first met but their 25-year relationship started with Riopelle showing up at Mitchell’s studio with “a huge bouquet of rolled canvases” as curator Michel Martin writes. Mitchell divided her time between New York and Paris from then on.

When she was gone, Riopelle missed her. When he lacked inspiration in oil, he turned to gouache and tried to follow the transparency and unique textural effect of Mitchell’s work. In a letter in 1956, he confesses to adopting her materials and technique: “I’m happier because ultimately (my work) resemble(s) your painting, my love.” Sans titre (La Fontaine) (1957) also reveals the complex bonds between them. Mitchell discreetly wrote in the upper left-hand margin of the painting “Le Laboureur et ses enfants, La Fontaine!!” referring to the well-known fable but also to Labours sous la neige, a work that Riopelle had recently produced. Mitchell kept the painting for a long time, as a message of affection for Riopelle. Riopelle stated, “Friendship is a special kind of solitude, a solitude split in two.” Their lifestyle was anything but lonely. They socialized a lot, people visited and stayed in their studios and they went out dining and drinking all night with friends.

The AGO’s exhibition follows a dual chronology focusing on points of mutual influence. As Martin says, “these two sensitive and extremely powerful personalities could not have evolved without being affected by the singular context of their relationship as it developed over the years.” Sometimes the artistic influence is unmistakable as in the pair of small-scale gouache on paper works (Mitchell: Untitled, 1958 and Riopelle: Gitksan, 1959) that share the same palette and gestural approach.

They were abstract painters but critics claim that both Mitchell and Riopelle got their inspiration from nature. Mitchell disagreed. She said: “I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me, and remembered feelings of them, which of course become transformed. I prefer to leave nature where it is, it is beautiful enough, I wish not to improve nature, I could certainly never mirror nature. I would more likely to paint what it leaves with me.” She was not interested in reproducing nature but in “painting the feeling of the space.” Riopelle stated in an interview, “Nothing abstract, nothing figurative. My most abstract paintings, according to some, are for me the most figurative, in the true sense of the word. Abstract: “abstraction,” “to abstract” “to derive from” … My approach is the exact opposite. I don’t take anything from Nature I move into Nature.” Mitchell and Riopelle shared the same vision, and their works were both infused by the powerful evocation of nature.

In 1954-55 Riopelle painted a series inspired by the Austrian Alps. Saint-Anthon (1954) is a bird’s eye view of the snow-covered peaks. The abstract landscape is built upon a large white background, unusual in Riopelle’s palette, interrupted by dark knife painting directly from the tube to give texture, and modified by occasional red and blue calligraphy. Mitchell’s Untitled (1955) uses similar colors. She catches a memory image and depicts it in fluid translucent strokes, with the presence of color at its center: a patch of dripping light-rinsed and storm-tossed blues skimming across viscous grey whites. It seems to be coalescing into the shape of a tree — Mitchell talked about mentally losing herself in trees — as the painter subverts the traditional relationship between figure and ground, never allowing the image to come together as a tree. Throughout her career, this tension remains inherent in ambiguous figure-ground relationships.

Energy and power radiates from Mitchell’s brushstrokes in Piano mechanique (1958). While the white background is present, bright colored lines and marks move in every direction, instead of a centralized composition, following the energy of the artist’s hand. She also changes her vertical canvas for a horizontal one, Riopelle’s preferred format. Riopelle also physically engaged in his works, as we can see in Landing (1958). He covers the entire surface with layers upon layers of strong colored paint, as he throws himself into the painting, sculpting the surface of the canvas until the paint seems to overflow — then he uses a knife to give texture to the paint and finishes it with a gloss to direct the light. He prefers to finish a canvas in one stretch, sometimes working 12 hours straight; as he said, “when I hesitate I do not paint, when I paint I do not hesitate.” Mitchell, on the other hand, made many sketches before painting.

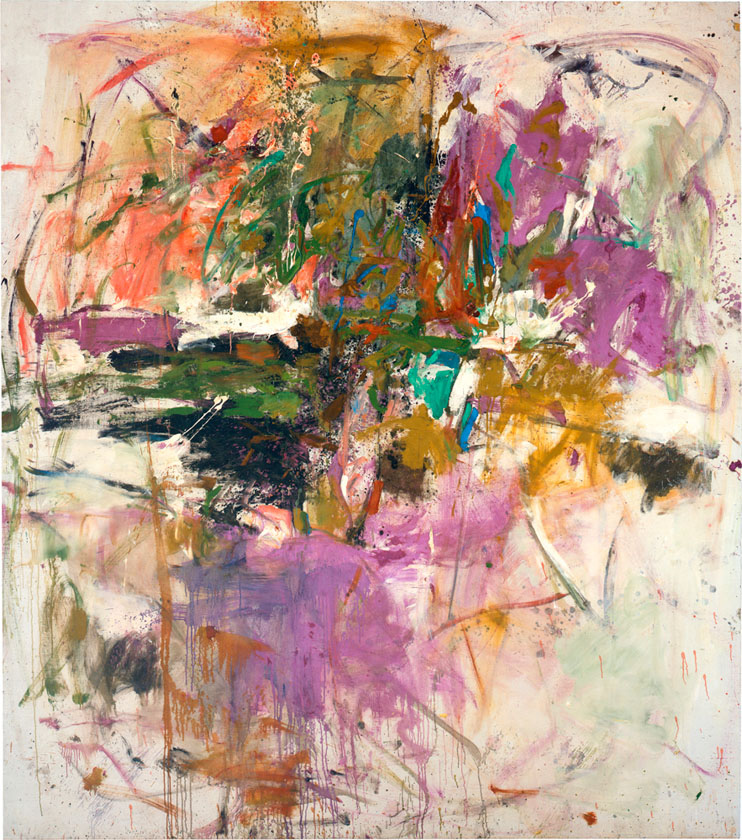

In the late 1950s Mitchell’s style and palette changed. The composition of Untitled (1961) is more tumultuous and now she allows gravity and paint to assert themselves from a loaded brush and create ghost-like patches. The paint is left to run till a certain point when the artist will regain control with overpainting of some parts. In vigorous, fleshy fists of paints she uses a rich palette of charged colors: greens, yellows, blues and blacks enriched with mustard yellows, blue-blacks, tangerines and the most beautiful violet, against a white background. As critic, Pierre Schneider wrote of this period, “The moments when everything falls into place is incredible. Panic, chaos, and anguish overcome.” Opaque and transparent at the same time, the composition seems to push into its white corners and grow in front of our eyes. Through her rhythmic strokes Mitchell wanted her paintings to have the feeling of poetry rather than a story. Poetry played an important role in her life; her mother, Marion Strobel Mitchell, was a well-known poet in Chicago. As a painter she often read poetry for inspiration before painting and titled her work after poems. In Mitchell’s pieces painterly intelligence goes hand in hand with passion and dedication.

The relationship between Mitchell and Riopelle was very rich, combining all the elements of life and art. They talked about art, their experiments, accomplishments and successes, their struggles and their ecstasy – their state of mind and their artistic practise. That must have been a wonderful journey for two such great artists. There was love too, both physical and intellectual. Throughout their journey together they crossed into each other’s territory, friendly, gently and lovingly but also screaming with anger. They were annoyed by unfulfilled promises, and not getting what they desired out of the relationship. Mitchell’s hope for a fully shared life seemed to be close to realization when they moved into a studio in Frénicourt, Paris in 1958 but it didn’t work out. Even after Riopelle’s divorce from his wife in 1962, the relationship between Mitchell and him remained turbulent and they both had many lovers on the side. Mitchell put her unhappiness into a few violent and angry paintings throughout these years.

The early 1960s was a relatively happy period in their life and their styles visibly intertwined. Riopelle got a boat, Serica, as payment from his New York dealer, Pierre Matisse, and they went sailing in the Mediterranean. Their large triptychs, both from 1964, show many similarities. They both build on the color of white, using a symmetrical structure, such that the painting on the left is mirroring the one on the right, so the panels seem to communicate with each other. The left and the right panel of Riopelle’s Large Triptych depict the rocks of the seaside in their whitish greyness with the buildings of the small villages in earthy browns, greens and reds, surrounded by the blue sky and sea as the colors shine in the strong sunlight. The middle panel departs from all reality and abandons strong colors, showing something like a map. Riopelle uses this signature technique so the different layers create a strong texture in which he literally carves the edges of the rocks. Mitchell’s favourite multi-panel format was the horizontal triptych composed of vertical modules. She liked the way the vertical divisions undermined the continued effects of a landscape. Girolata is a good example of this. In front of an atmospheric whitish background patches of mossy greens, dusty silver greens, cerulean blues, violets and all imaginable shades of grey cover the panels in a soft, dance-like movement. Here too, the central piece seems to unify the others into one, more balanced, composition. It feels like the metamorphosis of a landscape but Mitchell said she didn’t want to portray the landscape but to transpose to the canvas the effect of the complex sensation of her memories of the time she spent with Riopelle. When placed face to face on the walls in the AGO, these works illustrate the dialogue that developed between the two artists and compare Mitchell’s poetic and sensual gestures to Riopelle’s more virtuous spatial strokes. It seems that a sense of harmony had been archived.

But it was more likely an illusion. While their careers skyrocketed — Mitchell had her first retrospective in the Whitney Museum (1974), Riopelle became an international artist whose paintings sold for high amounts — the distance between them deepened. Mitchell, using her inheritance after her parents’ death (1969), bought Monet’s property La Tour in Vétheuil, where she settled for the rest of her life. Riopelle built a studio in the Laurentians (1974) and divided his time between France and Quebec where he fished and hunted. They still spent time together but less and less often and their styles no longer show the similarities of the 1950s and 1960s. Mitchell, accompanied by her dogs, enjoyed the solitude of her gardens. She dedicated the diptych, Un jardin pour Audrey, (1974) to her friend Aubrey Hess, who recently passed away. In the left panel, we are guided into a beautiful garden with light pouring in, flurries of blazing gold against a radiant white – a composition that reminds us of Monet, without becoming a still life or a landscape. The right panel juxtaposes the lightness of the left with a heavier composition and a darker palette. Together they seem to depict paradise lost and found, radiant with the love of nature.

The tension between the couple grew and Riopelle called Mitchell “Rosa Malheur” – Rosa Unhappiness. He started to spend more and more time in Canada. Mitchell painted Chasse interdite (Hunting is forbidden) (1973) to let Riopelle know that she doesn’t approve of his hunting trips because it takes him away from her and she misses him. Riopelle embraced Quebec’s vast landscapes with its wildlife, fishing and hunting, depicting First Nations cultures that resonated with him. The title of the painting Micmac (1975) or Mi’kmaq comes from the Indigenous peoples in the Gaspé Peninsula, but in French the word means confusion or disorder. It is a very intriguing work. As the story goes, the artist painted one of the panels then transferred it into a blank canvas. Then he extensively reworked both until they seemed to be different. The left panel has a shining dark area at the top contrasted with a matt white on the right. Darker, warmer colors on the left seemingly oppose the lighter, colder palette of the right. Both panels have hidden crosses (a reminder of Riopelle’s struggle with the Catholic religion) and the elements of the paintings are organized around them. Chaos rules the surfaces with a little bit hope in white light of nothingness at the bottom of the right panel.

In late 1974, when Riopelle stayed longer than usual in Canada, Mitchell visited him and created her Canada series, dominated by disorderly shapes of browns and greys. In Returned (1975) she reduced her palette and used almost geometrical shapes, echoing Riopelle’s tendency for structure. Riopelle in his Iceberg paintings also abandoned his rich color range, until only black and white prevailed (Iceberg No.3, 1977). As he said, “If I dared to paint my series of icebergs in the 1970s, it’s because the color white doesn’t exist in nature. If snow were white, no painter would be able to render it.” As later added, “In the arctic nothing is clear cut, all is not black and white. The sky, though, seems black, really black, and on the ground is not even white snow, there it is ice that is grey and transparent.” The paintings don’t give us any direction in these strange landscapes where white ice rules, distracted by the black calligraphy of cracks and trees under an overwhelmingly black sky. Meanwhile Mitchell, enchanted by nature in her garden, painted single sunflowers, weeds, rain and her favourite linden tree Tilleul (1978) with dramatic intensity.

They saw each other less and less often and when they did, they argued more, until their final separation in 1979. It was a stormy relationship by all accounts. They were both heavy drinkers, Mitchell was an alcoholic and often depressed. When drunk they became abusive, as many of their friends wrote: they were violent, crazy and scary. They were a perfect match, both in the strength of their characters and the quality of their paintings and above all theirs was a great love. The chemistry between them was strong, creating a shining glow of happiness sometimes and deep craters of anger on other occasions. Meanwhile their lives went on, and they both became icons of the art world in their own right. Their interaction can be compared to two stars shining at each other until, at some point, they parted ways, still rising, without outshining each other.

Together and separately, they lived an extraordinary life of extremities – nothing in moderation.

Emese Krunák-Hajagos

*Exhibition information: Musée national des beaux-art du Québec , Québec city, Québec , October 12, 2018 – January 7, 2018 & Art Gallery Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, February 18 – May 26, 2018