Black Power!

On view in the Main Exhibition Hall

Curated by Dr. Sylviane A. Diouf

The concept of Black Power was introduced by Stokely Carmichael and fellow Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) worker Willie Ricks in June 1966. Like no other ideology before, the multiform and ideologically diverse movement shaped black consciousness and identity and left an immense legacy that continues to inform the contemporary American landscape.

Perceived mostly as a violent, urban episode that followed the rural, non-violent Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power movement, which lasted only ten short years, had a more significant impact on issues of identity, politics, culture, art, and education than any prior movement. Reaching beyond America’s borders, it captured the imagination of anticolonial and other freedom struggles and was also influenced by them. Similarly, Black Power aesthetics of natural hair and African-inspired fashion, and the concept that black was beautiful, resonated worldwide.

Following in the Black Power footsteps, American Indian, Asian, women, Latino, and LGBT groups challenged the status quo, and the politics of group identity entered mainstream academia and society at large. One of the most lasting legacies of the Black Power movement has been the enduring strength of the Black Arts Movement. The cultural transformations brought forth by the movement left indelible marks on black aesthetics and visual arts, as well as on hip-hop and spoken word artists.

Thus, to understand 20th and 21st century African-American history, and ultimately American society today, it is imperative to understand the depth and breadth, and the achievements and failures of the Black Power movement.

ORGANIZATIONS

Black Power grew out of the political, economic, and racial reality of post-war America, when the possibilities of American democracy seemed unlimited. Black Power activists challenged American hegemony at home and abroad, demanded full citizenship, and vociferously criticized political reforms that at times substituted tokenism and style over substance. Some activists did this through a sometimes bellicose advocacy of racial separatism contoured by threats of civil unrest. Others sought equal access to predominantly white institutions, especially public schools, colleges, and universities, while many decided to build independent, black-led institutions designed to serve as new beacons for African-American intellectual achievement, political power, and cultural pride. Organized protests for Black Studies, efforts to incorporate the Black Arts Movement into independent and existing institutions, and the thrust to take control of major American cities through electoral strength exemplified these impulses.

The movement’s multifaceted organizations, from SNCC to the National Welfare Rights Organization, triggered revolutions in knowledge, politics, consciousness, art, public policy, and foreign affairs along lines of race, class, gender, and sexuality. It forced a re-examination of race, war, human rights, and democracy and inspired millions of global citizens to reimagine a world free of poverty, racism, sexism, and economic exploitation.

POLITICAL PRISONERS

The Black Power movement was made and unmade through encounters with the criminal justice system, especially the prison. Prisons were especially central to activists’ efforts as they drew on their own experiences of confinement to indict a broader system of white supremacy. Many of the movement’s strategists, theoreticians, and foot soldiers spent time in jail or prison. For some, prison was the consequence of their organizing. For others, it was where they joined and contributed to the Black Power movement.

The urban rebellions of 1963 to 1968 were often sparked by incidents of police brutality and saw thousands of people arrested. Activists resorted to study groups, escape attempts, newspapers, and legal appeals to challenge prison as both a metaphor for oppression and an example of it. But by the mid-1970s there was growing bipartisan support for increasing the severity and length of sentences. Thus began the rise of mass incarceration that would disproportionately impact the youth who had been the base of the Black Power movement. A half century later, the interrelationship between prisons, policing, and racism remains a central example of American inequality.

COALITIONS

The Black Power movement had a radical impact on grassroots organizing in poor communities of color and many white progressive circles. Grounded in the Black Panther Party’s core was its leadership in the international revolutionary proletariat struggle, a deep affinity for forming coalitions and alliances that transcended race and class, and a commitment to community service programs (survival pending revolution) as a fundamental element of human rights.

These groups demonstrated by way of their bold confrontational methods the egregious contradictions of American democracy and a shared vision of a society that valued humanity over wealth. Such facts are highlighted by the various conventions and conferences organized during the Black Power movement, including the 1967 National Conference on Black Power in Newark, New Jersey; The United Front Against Fascism Conference that took place in 1969 in Oakland; The Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1970 and the National Black Political Convention of 1972 in Gary, Indiana.

Delegates from an array of organizations gathered to write a new constitution that represented a united vision of a just and free society. These U.S. citizens not only called for a new nation but a new world that embraced solidarity, liberation, and tolerance for difference and diversity.

EDUCATION

A host of grassroots black educational struggles unfolded in the 60s and 70s. Schools and other sites of learning provided the critical terrain for battles over black studies, community control, and African-American identity. Insistence on black autonomy and internal development of African-American communities reshaped black educational outlooks. Many African-American educational struggles sought radical reform rather than incremental change, group progress rather than individual freedom, humanism rather than materialism, and political engagement rather than mere social mobility. They included cosmopolitan and internationalist perspectives, a reflection of revived interest in African cultural heritage and Third World movements.

Student rebellions erupted on scores of high school campuses. Small, creative institutions played crucial roles in the intellectual and cultural development of people of color, especially as public programs in urban centers fell victim to cutbacks. Alternative models rooted curricula in the lives and experiences of black people while giving programmatic structure to Black Power ideals.

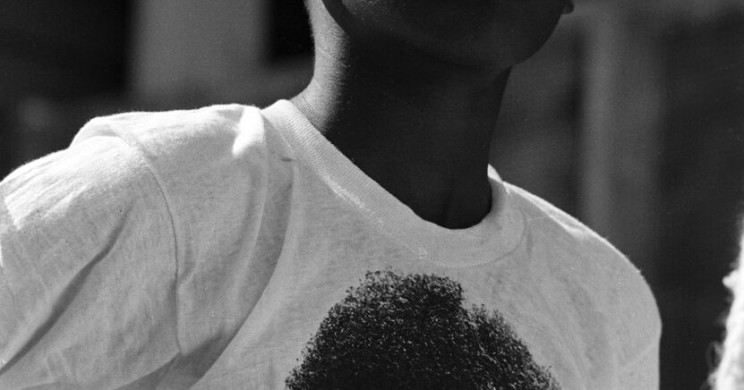

THE LOOK

In many respects, fashion was the most immediate and obvious marker of Black Power’s influence, while it simultaneously reflected the ideological diversity of the movement itself. Many younger African Americans, regardless of the degree to which they were politically active, donned Afros, African-inspired clothes, or sartorial inflections of militancy, often associated with organized black nationalist or revolutionary organizations.

Fashion was a clear declaration of what some called the “new black mood,” which swept Black America. The fundamental thrust of Black Power was black self-determination, and a very clear affirmation of black people’s humanity. To that end, racial pride was inextricably tied to the cosmetics of blackness.

By the waning years of the Black Power movement, the black press was no longer full of advertisements encouraging readers to get their skin as white as possible. Natural hair was not viewed as bizarre. Black pride remained elusive, but no moment had pushed black people closer to it than this era.

POPULAR CULTURE

Athletes joined artists and community organizers in linking Black Power to their everyday experiences. Muhammad Ali was one of the major figures to address how his athletics reflected his abilities as a black man to think independently of a white sports industrial complex. The Olympic Committee for Human Rights used the 1968 Olympics as a platform to support the agenda of the Black Power Conferences. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar refused to play on the Men’s Olympic Basketball Team to protest inequality and racism. Remembered through the iconic photo of their medal ceremony, Tommie Smith and John Carlos bowed their heads to pay respect to fallen warriors of the black liberation struggle, and held their gloved fists in the air to represent black power and unity.

Martial arts schools served as critical sites for artistic production, resistance, and empowerment. Organizations such as the Congress of African People, US organization, the Nation of Islam, and the Black Panther Party practiced martial arts to teach body development and strengthening, self-defense, and creativity. Images of black martial artists also became popular on screen due to the genre called Blaxploitation, Hollywood’s version of black urban life.

BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT

If, as a number of scholars have commented over the years, The Black Arts Movement (BAM) was the cultural wing of Black Power, one might also say that Black Power was the political action wing of BAM. In truth, BAM and Black Power were not so much separate entities, but rather, as Larry Neal put it, “concepts” of, or ways of coming at, the black freedom movement. In that way of thinking, art was (or could be) political action just as those activities usually considered to be political were a sort of art.

BAM changed how people felt that art should be circulated. The BAM imperatives of art for, by, of black people in the communities in which they lived as opposed to in elite museums, theaters, or concert halls in which they often felt unwelcome, opened up the cultural landscape for art and arts institutions supported by public money and other resources and aimed at grassroots communities. Not only did the BAM reach millions of people through its journals, presses, theaters, murals, festivals, and television shows during the 1960s and 1970s, but it left a lasting imprint on our sense of what art is, what it can do, and who it is for that remains with us to this day.

SPREADING THE WORD

Whether cultural, political, social, or academic, written texts by Black Power artists and activists was unprecedented. Periodicals, newspapers, books, publishing companies, and bookstores empowered the community by providing historical knowledge, political and revolutionary awareness, and cultural pride.

To bring their message directly to the communities they served, organizations published their own newspapers. As expressions of the interconnectedness of Black Power and the Black Arts Movement, they were often literary and political, covering local and international issues and presenting poetry, short stories, and graphic arts. Small publishing companies offered an outlet to poets, novelists, educators, scholars, and activists.

Black bookstores, such as The African National Memorial Bookstore and Liberation Bookstore in Harlem, did more than sell books. Drum and Spear bookstore in Washington, D.C. added a publishing company, Drum and Spear Press, and a Center for Black Education to its activities and opened an office in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. These stores acted as cultural, political, educational, and social centers where the community could take classes, meet authors, militants, and visiting activists. They became sites of education, creativity, and resistance.

BLACK POWER INTERNATIONAL

Black Power activism erased national boundaries as its strategies and tactics proved adaptable in a variety of circumstances. Black Power became global, part of narratives of commerce, migration, imperialism, and cultural exchange. It was an international movement that, in voicing common elements within the experiences of African and African-descended diaspora peoples, provided a framework that helped define their grievances and goals. Additionally, it supplied a vocabulary, though spatially and culturally removed from the conditions of African diaspora life, and engaged in struggles with different objectives, found meaning in the interpretations conceived through Black Power’s set of values and practices. Black Power’s legacy is the ongoing history of the worldwide determination to contest all forms of domination and injustice.

For exhibition-related inquiries, email schomburgexhibitions@nypl.org.

Opening soon. February 16th, 2017. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

OPENING February 16, 2017 on display through October

Black Power!

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

515 Malcolm X Boulevard at 135th Street

FREE

Courtesy of The New York Public Library