Travel to the edges of any major European city, and you reach placid suburban hell. This is true even for ultra-civilized Copenhagen. The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in the suburb of Humlebæk is reachable in under an hour by train, from which you see the city ebb, flow, and dissipate. Tucked inside an otherwise unassuming street, it treats us to a mock-Riviera villa with slick modernist appendages. Through the garden, luscious and perfectly kept, you are confronted by the sea, the Øresund. The gallery’s promotional material emphasizes the beauty of the location, claiming that Louisiana is able to strike a rare balance between art, architecture, and nature—but it is hardly unaffected. Could there ever be a better environment to experience the artistic career of celebrity peace activist Yoko Ono?

Louisiana provides a minor relief to the full philistinism characterizing modern experience, but there is something not quite right about this setup. For one thing, it’s a bit too civilized. On a sunny afternoon, one can sit in an ergonomically correct chair at the Louisiana Cafe, basking in the sea air in total peace, amused by fellow visitors’ perfectly behaved children. Does this not play out in the gallery experience, too? Is it not the case that spectator and artwork, subject and object, mutually internalize the calm? If yes, does the confrontation with the art-object turn into a crude exercise in lifestyle aestheticism? A rather surprising second problem is that, when you go to Louisiana, you enter through the gift shop. The banality of shopping physically impedes our access to the artworks themselves. The gift shop is thoroughly tasteful, but the problems with this should be self-evident. What better way to mark the full domestication of Fluxus, or, by extension, conceptual art than this?

Ono’s Half-A-Wind Show consummates these problems. A retrospective of her half-century in art and music, it is heavy on biographical details. It gives us a celebratory overview of her personal, political, and creative life in big bilingual panels before we enter the exhibition-proper. It puts these details in their world-historical context, which rather inflates Ono’s significance. It is unclear if we are supposed to believe that she lives up to the Romantic cult of individual genius. How would this work, exactly, when she is such an advocate of audience participation and the death of artistic authorship? It is right to think of Ono as one of the surviving participants of an era of unsurpassed creative response to social and political crisis? It is difficult for those of us born during its aftermath—the long, ongoing anti-1960s—to look at that time with the misty-eyed nostalgia of our baby-boomer predecessors.

Half-A-Wind Show acts as a convenient sample of its failings. It commits itself to the same problems that afflict much contemporary art. It prefers to try to be overwhelmingly entertaining rather than to begin to pose interesting questions. It is not enough to say that the sheer amount of work here is at best, distracting, and at worst, muddling. The show includes one hundred or so works, from ready-mades and paintings, through films, installations, photos, drawings, and textual works. It is impossible to provide a full assessment of it all. Instead, we have to limit ourselves to pointing towards the docility of these works, their lack of any truly critical power. There are two key examples of this.

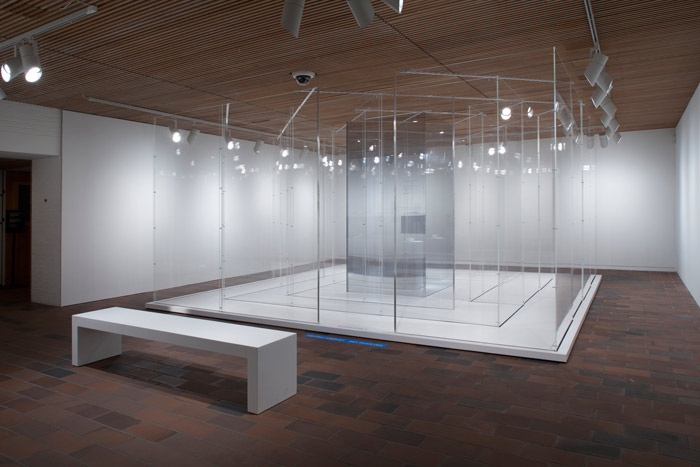

Yoko Ono, 18 (glass chambers). Half-A-Wind Show: A Retrospective. Installation shot

Photo: Brøndum/Poul Buchard

Credit: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

First, the gallery experience itself stifles the staple Fluxus concepts of interaction, performance, and ‘intermedia’. People are often understandably nervous about physically engaging with art-objects, even if the work itself claims to invite it. In this case, however, we are not actually allowed to interact with the supposedly interactive art. 1966’s Ceiling Painting, (Yes Painting) provides us with one such example. The work itself comprises a ladder, which one is supposed to climb. At the top is what looks like a trapdoor with a magnifying glass attached. It is, in fact, a panel upon which is painted the word “YES”. The problem is that Louisiana is here acting as the steward of the art collection of Detroit’s Gilbert and Lila Silverman. This is private property. Trespassers will be frowned upon and politely asked to leave.

Second, the art-going public still tends to treat works of art with a quasi-religious solemnity. This is precisely the sort of fluttering bourgeois anxiety that movements like Fluxus tried to challenge in the first place. The whole point of Fluxus was that it tried to make art fun. Perhaps this is why the noise from the twenty-five minute long 1970 video piece Fly is allowed to interfere with the earnest silence irreverently expected of the ready-made Apple from about 1966. Fly follows the adventures of a fly as it skirts the contours of a naked female body. It crawls through pubic hair, ascends the nipple, caresses the lips. Accompanied by a bizarre, jarring fictional buzzing sound made by the artist’s own voice, it blinds the male gaze as it goes. Apple, meanwhile, comprises a plexiglass stand with a brass plate reading “Apple”. At the top is an apple. Between them, there could be some curatorial crosstalk between nature and its manipulation, between disgust, animality, and the question of the erotic—Biblical origins of human self-knowledge.

Of course, this could just be a coincidence. It could be a moment of flux amid the sheer superficiality of a show that refuses to question the disappearance of beauty in art, the reduction of high conceptuality and anti-representationalism to pure surface, or the apparent canonization of Ono herself. The only question it prompts is “what’s the point?” The only answer we are likely to receive is that there isn’t one. It might be best simply to enjoy the view.

By Max Feldman