A strawberry candy-wrapper, recreated extra-large in the bold, commercial colors of the original throw-away, hangs just inside the entry; it is a cheerful welcome to this exhibition, and the shift in scale startles me—the painting is about the size of my head, and this makes me think of the urgency of a child’s valentine offering: in matters of love, bigger is better. In another room, a fat phone book, splayed open as if in a (failed) attempt to make a paperback Christmas tree, then doused with layer upon layer of greyish paint, is installed near the ceiling. This object is beautiful and disturbing, it looks very real and yet fictive; I think of a cyclone, I think of Ezekiel’s Wheel, I think of it in the making—going from wet to dry, again and again, picking up dust and smog as evidence of its history.

These objects in John Burtle’s exhibition, Support Constructs at Michael Benevento Gallery, are made mostly from acrylic paint; some lack any additional support beyond the paint, and the paint objects that do employ traditional supports do so matter-of-factly, in a way that seems not interested in old-fashioned art conversations about “the support.”

Surveying the first room, I see before me on the ground the sculpture Banana Skin (2012), withered and blackened as though by age; it reminds me of corny old movies with a shuffling tramp, and of clowns (a little bit), and of lunch. This banana skin has darkness and humor, it has the seriousness of a thing that is made by hand. The scale is funny though, smaller than it should be (in my mind) and as I look down I feel like Lewis Carroll’s Alice, with her long, stretching neck. I want to be careful of it, not because the sculpture is small, but because it has made me feel big and unstable on my distant feet. It’s curious to me that I am made to feel fragile by this diminutive work of art, which through a kind of transference has increased in substance relative to me, if not in size.

A large painting hangs to my left, this looks like a landscape, with cartooney elements made from thick layers of acrylic paint collaged onto unstretched, open-weave linen. But the various parts, including a volcano, lustily blowing red smoke, a saguaro cactus, a rain cloud, and also a separate painting, seem organized to tell a story. The composition feels allegorical, as do the title(s): Thanks, But an Umbrella or Something Would be More Useful (2013), for the larger piece, Untitled (Everything is not Okay) (2010-2013), and Oooof for the combination. Each part of this community of paintings is independent, and yet each relies for support on the other parts; directly, through adherence, and indirectly, by association.

She Loves Me, She Loves Me Not, She Loves Me, She Loves Me Not… (2013) is an example of yet another type of strangeness in Support Constructs. This lovely and lush array of purple flower petals appears straightforward as I approach it, “Ah, I see. He painted the petals on plastic, peeled them off, and stuck them on this circular panel, beginning at the center.” The scale of the work is enveloping. Without horizon, it also feels without edges when I stand before it; and the patterning of the petals creates visual waves, similar to the repetitive patterns in Bridget Riley’s paintings. They are a strong attractor on my center of gravity. Once again, I am made to feel, or rather, allowed to feel unstable by this artist’s work. I choose to say, “allowed” because this is a pleasurable instability. Burtle offers his experience as being possible through the objects in this show; as an artist he uses persuasion, not force.

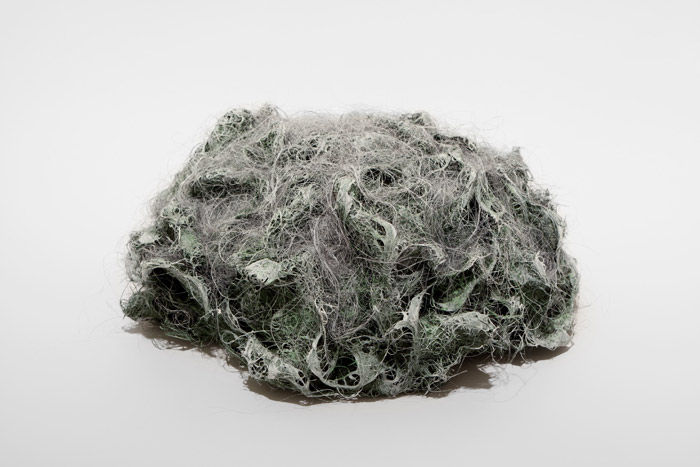

John Burtle, Hairy Succulent, 2013. Acrylic paint, hair, 12 x 12 x 4.75 in. Image courtesy of Michael Benevento Gallery.

Among Burtle’s other concerns in this exhibition seems to be the queerness of art objects—queer in the sense that a thing is unsettling. The 3/5 scale of Banana Skin is one example of this strangeness, another is the sculpture Hairy Succulent (2012), a curious representation of a desert plant that grows low to the ground, and is hirsute in aspect. I look at Burtle’s sculpture and I don’t want it be to real hair, I want it to be some material the artist crafted. But it is hair, real hair, collected from a barbershop, and it is all the more creepy because of this.

Curiously for a show as dedicated to object-hood as Burtle’s show is, I think the matter at hand is better understood through language, and by considering his objects in relation to each other, along with the exhibition title. To draw from Wikipedia, “A construct in the philosophy of science is an ideal object, where the existence of the thing may be said to depend on a subject’s mind. This as opposed to a real object, where existence does not seem to depend on the existence of a mind.” A construct might be a real thing, but it will be a concept, and not an object.

An exhibition is as much ideas as it is objects, Burtle reminds us of this with his title. In this way Support Constructs serves as an emphatic, if gentle reminder of the fluid nature of identity, both human and artistic. While our essence (whatever that thing is) remains essentially always the same, we are changed by our association with others. In other words, to speak in human terms, a friendship is greater than the sum of its parts.

By Geoff Tuck