How persistent is the wish to somehow find a human face in whatever kind of art—to see a real presence there that invites us to know its secrets and enjoy its troubles?

How powerful is that illusion of a real presence, when a ramshackle and effaced effigy, an ugly or beautiful scarecrow clothed and stuffed with snips of film, contradictory statistics, detritus of consumer goods, notations from books read and transactions made, can be mistaken for a double of the artist?

Within a week of my first viewing of John O’Connor’s October 2013 exhibition at Pierogi Gallery, “The Machine and the Ghost”, I saw a special screening of Jean-Luc Godard’s rarely shown 1994 self-portrait film JLG/JLG. The coincidence of the two triggered a recognition. In both works, I saw an aggregation of parts that seemingly taps the yearning for contact with something intimate, an actual person. In each case I found works that, seen clearly, leave that hallucination undone.

In JLG/JLG Godard’s figure and words materialize and disappear throughout the film. Images are overlaid with a shifting litany of onscreen texts and voiceover. JLG/JLG moves both toward and aside from the actual Godard via displacement, redirection, substitution—a simultaneous presentation and disintegration of the presence of the author and subject tracing paths around autobiography. There is a sequence concerning a blind film editor. As the editor snips and rejoins sections of film according to the cryptic verbal instruction she is given by Godard, who is off screen, we witness a formal reordering of recorded data (captured images of the subject, of time, light, space, i.e., film). One system of sequence and incident is rearranged by being conjoined with another system. That other system is an arcane or maybe arbitrary numerical order injected from outside the frame, a re-encoding of the data, a shuffling of evidentiary exhibits.

In “The Ghost and the Machine”, as with his previous exhibitions, John O’Connor’s works track and re-organize information and events. Pieces of evidence are delayed, mingled, organized, toyed with, compared, made graphically visible, made invisible as codes.

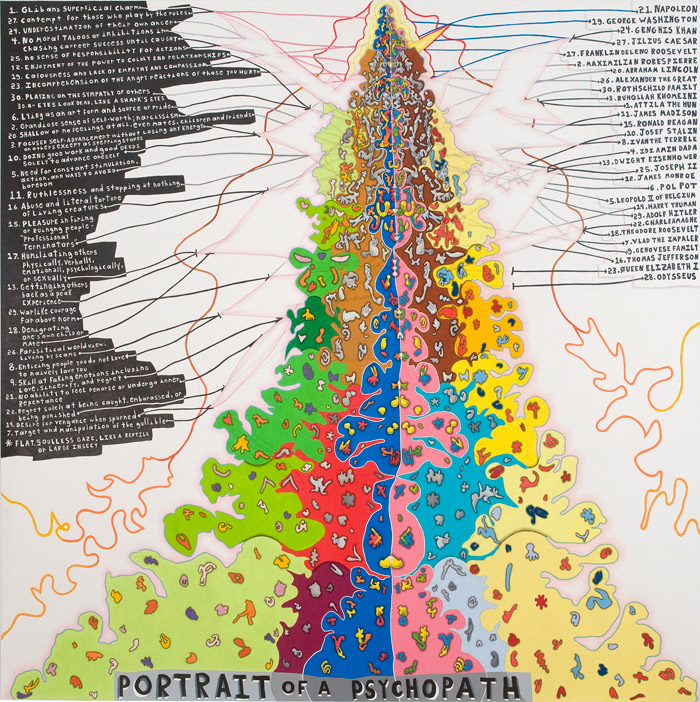

There is an additional, emergent sense of a persona in “Ghost and the Machine” that seems new. I have observed people asking O’Connor if he is the Psychopath described in Portrait of a Psychopath, if his drug and binge cycle narrative Butterfly is a true story, if his “Dear John” exchange of emails with “Beyonce” in Love Letters (Diptych) is real. Use of the first person in such text-based works and the deployment of photos of himself for his sunspot series create the illusion of a reveal, an unmasking of the personal.

In a series of identically-scaled photographs titled by their dates, patches that resemble huge lesions or birthmarks blossom across O’Connor’s face, extreme and shocking. He seems vulnerable and tenuous, maybe desperately ill. But the marks are only photographic records of the sun’s activity, superimposed on the face, following a logical calendar-like system. The personal image is divorced from intimacy in order to be fully engaged in the violent play of objective content. Everything is factual, but the implications we might read are not true.

The artist has also certainly deployed phantoms in these works, in the form of chatbots, which converse in exchanges transcribed in text-based drawings. Among these, and hovering over them, a phantom rises up in the guise of John O’Connor himself, just as for a long time now the knots of graphic information in his data-driven works have sometimes tended to suggest figurative apparitions, as in Kooky Yoga, 2005. Before this exhibition, though, the personages or chimeras evoked did not particularly become him, nor did they usually tend to give rise to something existing off the paper, wanting to occupy real space. Interestingly this new development coincides with O’Connor’s very convincing deployment of fully three dimensional works, embodied as, in one example, a helical loop, made of epoxy, writhing in roughly the shape of an infinity sign, a snake of words, choking on its own tail (Strange Loop, 2012).

O’Connor seems quite alert to registering what are self-evidently problems of this historical moment (as is Godard in his later films), the same conditions noticed and tracked by science, in the media, by political structures, by the culture. The spectrum of difficulties observed really pertains to O’Connor as an individual only in the sense that it is conditioned on the chance location in time (history), space (geography), culture, and genetic inheritance that the artist as observer happens to occupy. We all now exist in an information reality that includes access to a radically expanded quantity of data points (facts but also an expanded field of lies and tricks). The works perhaps act out an attempt to deal with this with objectivity and a desire for a factual grasp, where confessions of personal emotional responsiveness and angst are not really the point, but are factors among many. They are disturbing and complicating factors, as they shade and distort a picture that’s already permanently unstable. The point seems to be, at least partly, to locate accurately that constantly moving hairline juncture of banality and crisis: the present.

By Ken Weathersby