Irena Jurek: When I look at your work I think about how it’s in dialogue with ancient ideas and the origins of abstraction. Kandinsky is often accredited with having invented abstraction, but it’s existed for so much longer than that.

Evie Falci: If you look at Paleolithic art, it’s filled with spirals and dot work, and in a way where it’s covering the whole surface. There is a way of articulating or illustrating the immaterial world through these forms, a way that I find very exciting.

IJ: Your work also seems to reference a pagan ideology that predates Judeo-Christianity. Niki de Saint Phalle comes to mind. All the circles remind me of the ancient idea of continuity. From an Occidental standpoint, people tend to think of life and death as separate. It’s actually more of a life-death-life cycle.

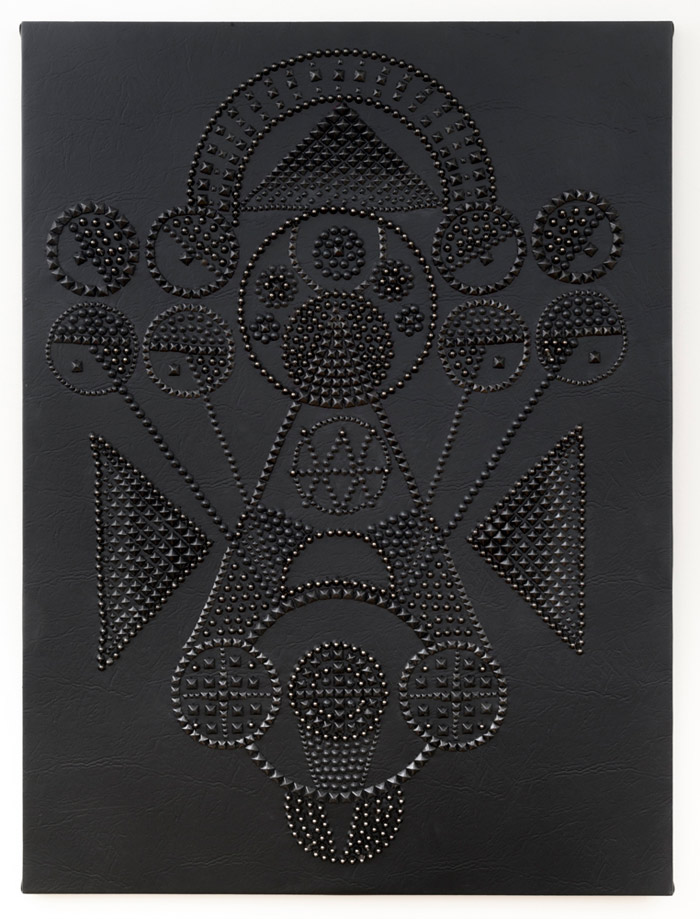

EF: It’s a wheel, definitely. Circles are the most perfect shape. It’s in way more related to a feminine depiction, but it can also be very cosmic, celestial. We can talk about what a mandala is and how it functions as a tool for journeying. I hope that these function as portals or stimuli for having that sort of experience.

IJ: They also remind me of Persian rugs. There’s this intense labor that goes into them and there’s so much complexity. At first you look at them and it seems as though the patterns are repeating and that there’s symmetry—but there’s always something a little bit off. There’s an idea in a lot of rug making, that the rug maker leaves a few flaws. Not necessarily a flaw, but…

EF: There’s an acknowledgement that a human being can’t create a perfect thing. That, that’s only done by a divine source, so they intentionally make something off or leave one part undone.

IJ: The funny thing is that nature often leaves things off, too! The idea of perfection is so elusive because the world is so deeply imperfect.

EF: Right. Well, it’s very important to me that these things look like a human being made them, that they’re not machine made, and that my individual hand is present. These are objects that need to be seen in person.

IJ: That’s important, since the visual experience is often taken for granted.

EF: It’s very important to be making objects that really need to be experienced in person, and to be making tactile things that actually exist in the real world.

IJ: There’s this overwhelming power to your work, because it commands your attention; it’s very celebratory and ritualistic.

EF: Well, that reminds of this text, Heaven and Hell, by Aldous Huxley. He basically talks about visionary experience first through mescaline and then through art. He talks a lot about precious materials like gems and gold and why human beings value those things. It’s because they’re precious and rare, but if you think back to the ancient world, these materials were the most brilliant and shiny and colorful things. They were thought of as being keys to some sort of heavenly or otherworldly realm. Rhinestones are obviously thought of as the poor man’s diamond, but because of the way they reflect light and the brilliant nature and color of the gems, it stimulates the eye in a similar way, and it’s riffing with stained glass windows.

IJ: I was actually going to say that these pieces look very much like stained glass windows. And stained glass windows were intentionally created to evoke this transcendental experience for people through the use of translucency and the way in which the light played or refracted.

EF: Exactly. Beauty is obviously important in this work and in my personal relationship to thinking about the power that beauty can have in a way that isn’t just superficial. Yet I’m taking the most superficial materials and trying to make them really serious.

IJ: It’s almost subversive to be thinking about beauty at this point, just because it’s been shunned so much. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that American culture is so largely based on both Protestantism and pragmatism. This pervasive push towards pragmatism attempts to eliminate anything that isn’t seen as the essential core.

EF: So, I’m working with rhinestones on denim and studs on leather, which is a form of embellishment. It’s decoration and you could say it’s almost superfluous in terms of the added adornment of bedazzling or studding your jacket. And maybe that’s why it’s perceived to be trashy in a way, too.

IJ: But, I think that that’s very essential to the roots of culture and civilization in general. Adornment has existed from the beginning.

EF: Of course, it’s a way of identifying you and your tribe, and what tribe you belong to—as well as what your values are and who you are as a person.

IJ: What were you trying to achieve in your current solo show at Jeff Bailey?

EF: I’ve been working with these materials for quite a long time. In this body of work I was trying to really narrow my focus, through making up these rules for myself, like limiting the palette in a very direct way, and also playing a lot with the negative space in the forms. The negative space in the forms becomes as important as each of the additive parts of the painting. They each have a mandala shape, where there’s a central point that emanates outwards, and even if it’s not symmetrical on four points, it’s reflective in its symmetry. They’re all, some more so than others, relating to traditional tapestry, rug work, or mosaic work.

IJ: This dialogue with crafts traditions also makes the work feminist, the same way that the feminists tried to remove themselves from the male tradition of painting in the seventies.

EF: Oh, yeah! Pattern is obviously very important in this work and its relationship to textiles and getting out of the heroic traditional type masculine painting.

IJ: There’s definitely a dialogue with AbEx in that the scale is bodily, and it reminds me of walking up to a Rothko. What you’re doing is similar to the way that the feminists in the past, like Lee Bontecou would subvert canvas by creating these intensely strong vacuums and voids.

EF: Oh, she’s my home girl! Love her!

IJ: And what you’re doing with the denim and the leather, I think that that’s such a conscious decision. There’s this celebration of femininity through the use of adornment and referencing these crafts traditions, and I feel that that’s really important because a lot of women are shying away from Feminism right now.

EF: Oh, well, God. How could you argue with what feminism is, and if you’re like “I’m not a feminist,” then you’re giving power to the people who have slandered that term and made it a dirty word.

IJ: The women who are rejecting feminism now, don’t seem to realize that they wouldn’t even have a platform to speak from it wasn’t for the feminists of the past who laid out the grunt work.

EF: People don’t have a memory of what it was like at an earlier time, and they take it for granted, this world that we are in now, except that there’s still such a divide. That’s why I want to make such aggressively feminine, aggressively beautiful paintings. At the same time, I don’t want to make vagina art! I don’t know—maybe these are cosmic pussies?!

IJ: There is still such a tendency in so much of the art world to downplay the importance of work that is feminine.

EF: Well, there was the pattern and decoration movement in the eighties, and this work is tied to that as well. Textiles and patterning are also associated with women’s work and feminine work. In the text, Ornament and Crime, Adolf Loos, is not specifically talking about women but you could read it this way too. He’s mostly talking about “savages” from Papua New Guinea who are involved with tattooing, piercing, and decorating their everyday objects. He claims that civilized people shouldn’t need to do that, and he fetishizes straight lines and unadorned surfaces. It’s a text that makes the case for modernism and imperialism.

IJ: Modernism has always struck me as coming out of an ascetic Puritanism.

EF: Totally, and this work is very anti that as well, being “more is more is more!”

IJ: It’s very problematic to me, the way that previous generations looked at abstraction with such unquestioning faith and idealism.

EF: That it’s a universal language that can be read by all?

IJ: Yeah, or even that’s it’s removed from the corporeal filth of actual existence.

EF: In a way, I do believe that abstraction can function that way, and maybe because these materials are so populist, that there’s already a very open point of entry for engaging with this stuff. That’s why I love outsider art and ancient art because it comes from such a place of fervent desire and an undeniable need to make, that I find lacking in a lot of work.

IJ: A lot of work almost begs permission for aligning itself with an academic dogma. So many artists still talk about demystifying art, and I feel like that may have been interesting twenty years ago, but it’s no longer relevant, because our ideas have progressed and our conception of the world has become more pluralistic and complex. I almost feel like we need to bring the magician back!

EF: Hey, I’m here!