There is a perceptible, unidentifiable energy that permeates the Picasso Sculpture exhibition on the fourth floor of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Phones snap pictures; viewers speak in enthusiastic whispers. And amongst the excited crowd: an invaluable collection of sculptures that catalogues 62 years of an artist’s life. The layout of the exhibit guides the viewer through time to 1964 from 1902, relaying Pablo Picasso’s artistic progression from bronze and wood cubist sculptures of his early years to twisting sheet metal structures that cap his career.

In the middle of this story is a rupture in the narrative: Gallery 7, The War Years, 1939-1945. It is a moment of pause from the abstract, celebratory autobiography of modern art’s golden child. The pieces displayed within The War Years gallery reflect the harsh realities of Europe in the 1940s and of Picasso’s specific experience as an artist in German-occupied France during the Second World War. The spatial organization, individual displays, and overall tone of the gallery reflect the curators’ desire to portray the morbidity of Picasso’s War Year pieces in a concise, minimalistic manner.

Upon entering Gallery 7, a shift in lighting signals a change in mood from the past three decades of Picasso creations. The previous room—Gallery 6, The Boisgeloup Sculpture Studio, 1933-1937— displays under bright lighting a set of colorful interpretations of the human form and the natural world. The room succeeding the War Years—Gallery 9, Vallauris Ceramics and Assemblages, 1945-1953—echoes the sculpture of Picasso’s Boisgelup Studio years in both tone and form: vases painted with controlled, energetic brush strokes; blooming plaster flowers in terracotta jugs; a miniature figure of a woman reading in a suggestive position.

But Gallery 7 is dark. The lighting is precise to the point of ascetic; each work receives only the careful stream of a pointed spotlight. As patrons depart Gallery 6 their voices drop as they succumb to the visual cue of a dimness that whispers suggestions of silence. Entering Gallery 7, the respectful, but audible, excitement that pervaded the last six rooms melts away, replaced by a hushed reverence for The War Years.

The sculptures of the War Years represent Picasso’s struggles as an artist under Nazi rule. They represent the somber social mood of a France infested with foreign soldiers. But more than anything, they represent Picasso’s attempts to push back against the social climate through visual commentary. The very medium through which Picasso relays his message is a rebellion; he casted some of his sculptures in bronze, an important commodity that the Germans reserved only for producing ammunition. Picasso also subverted German authority by refusing to conform to the accepted standards of art. In an audio guide provided by the museum, an exhibit curator explains that Picasso was deemed a “degenerate artist” by the Germans, meaning he was banned from exhibiting or publishing his work.

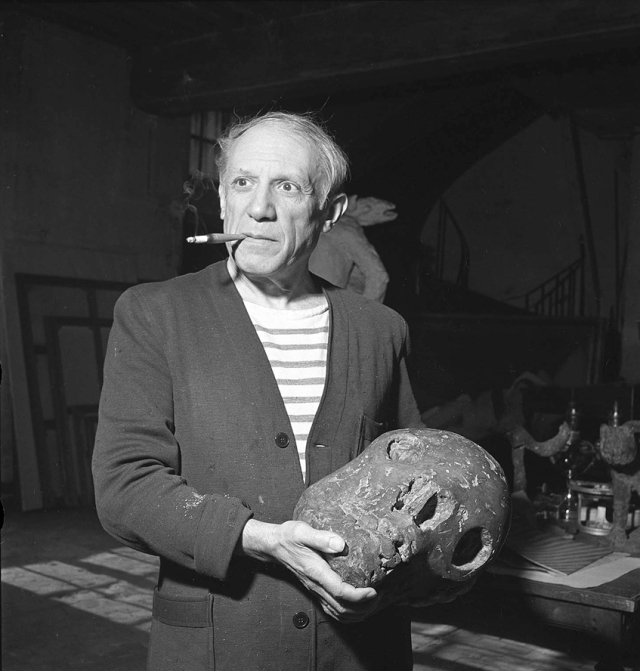

Picasso comments on his environment of moral ugliness by reproducing it in his work rather than attempting to cover it with shades of false beauty. Death’s Head, a 1941 work in bronze, symbolizes Picasso’s quiet defiance and his desire to acknowledge his day’s darkness. The sculpture portrays a lifeless and misshapen human head. Two bloated sockets lay where the eyes should rest. A gaping hole lies where the nose should protrude. Gashes from a carving instrument mar the forehead. These disfigurations are not products of the piece’s decay over time, but rather, they are purposeful imperfections inflicted by Picasso to embody the atmosphere within which he worked.

Gallery 7’s display of Death’s Head highlights Picasso’s masterful explication of the grotesque. The piece rests on a black block, and the dark head coupled with its dark background mutes a sharp spotlight. The head appears stoic without an accompanying body—a morbid, yet noble reminder of the evils of humanity. The curators craft a chillingly tranquil scene, and it is as if Picasso meant for Death’s Head to be rendered to the world as such: a decapitated entrée of despair served upon the dinner platter of a museum’s squeaky-clean podium.

Adjacent to Death’s Head rests Head of a Woman, the first work of The War Years visible upon entry from Gallery 6. The piece rests on a podium, roughly four feet in height, against a wall that stands alone in the middle of the gallery. The curator’s decision to display Head of a Woman as the introduction to The War Years fits the room’s chronological organizational scheme; the work was finished in 1941, the first of Picasso’s years in his new studio. However, the work also serves as a thematic segue from the playful cubism of the Boisgeloup Studio sculptures to the serious subject matter of The War Years. Less offensively grotesque than Death’s Head, the Woman and her enlarged, disproportionate features still manage to convey Picasso’s abstract aesthetic language that pushes against the accepted artistic style of his time. No clear political meaning or social commentary can be derived from the work, but it serves as an effective transition piece, echoing the thematic framework of Gallery 6 more closely than the other two sculptures from 1941: the first, Death’s Head and the second, Cat, a warped representation of a cat in bronze.

The layout of Gallery 7 connotes a purposeful geometry. Whereas the other galleries of the exhibit scatter their pieces about open floor plans in a seemingly unordered manner, the pieces of this gallery are situated in equidistant length from a central standalone wall. Other galleries of the exhibit boast nearly twenty pieces while Gallery 7 holds only ten. Three of these ten sculptures comprise a triptych in the back corner of the room, leaving a sculpture on both sides of the central wall and five sculptures positioned throughout the room. The lean offering of The War Years’ gallery allows each work to breathe its own story into life. Death’s Head is so evocative partly because the piece is visually isolated from the nearest sculpture by a few yards. Furthermore, the sparse layout of the room reflects the feelings of emptiness that Picasso himself must have felt while creating his works in German-occupied Paris.

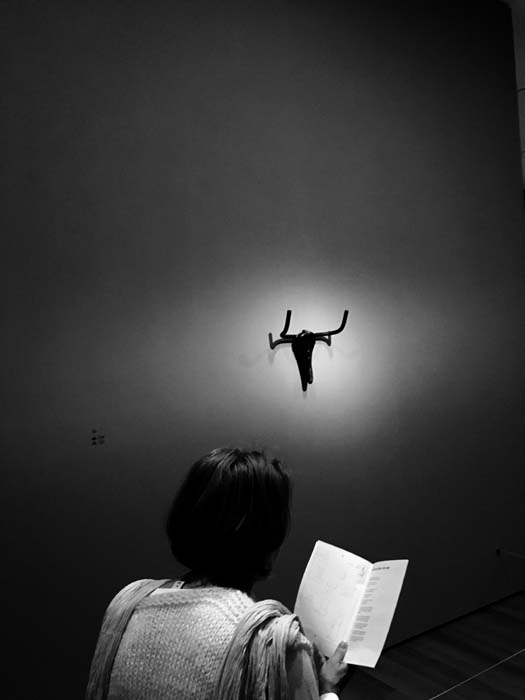

Aside from spacing and lighting, the curators tell Picasso’s story by utilizing the walls—or more accurately, by not utilizing the walls. Traditional galleries display their work against white walls with descriptive text beside the piece. Instead, The War Years room has gray-painted walls, and the wall text is replaced with a monochromatic, minimalistic pamphlet that gives basic information on each sculpture. These two unique curatorial decisions reinforce the somber tone of the gallery, emphasizing the lack of bright color in Picasso’s War Year pieces. The choice to forgo wall text mitigates visual distractions and allows the viewers’ attention to rest solely on the gallery’s pieces; the room’s energy bounces from sculpture to sculpture and is not cheapened by unsightly, cluttered chunks of text.

The curators do indeed use two of the gallery’s six walls to showcase the sculptures that necessitate mounting. The three sculptures in the far right corner of the room from the primary entrance (Head of a Dog, Death’s Head, and Goat, 1943) seem to be afterthoughts by the curators. The unassuming two-dimensionality of the triptych’s paper form relegates the trio to the back of the room. However, the curators display Bull’s Head, a sculpture no larger than a tennis racket, alone in a prominent position on the backside of the central wall. Bull’s Head is decidedly random in the context of The War Years—it is a simple assemblage made from a bicycle’s handlebars and seat. However, its placement on the central wall provides a moment of levity amongst the heavy subject matter in the room, and it embodies the powerful spirit of creativity amidst a time of turmoil.

Pablo Picasso, 1942, Tête de taureau (Bull’s Head), bicycle seat and handlebars, 33.5 x 43.5 x 19 cm, Musée Picasso, Paris

More generally, Bull’s Head emphasizes the simplicity, universality, and accessibility of art; one of the most renowned creators of all-time harnessed a childlike imagination to craft a work of art from old handlebars and a bike seat. The curators echo Picasso’s universal appeal in their desire to present the show to a wide-ranging audience. The printed informational pamphlet appeals to an older, more traditional audience, while the audio guide can be accessed on a smart phone by more technologically savvy museumgoers. There is even an audio guide made specifically for kids.

Pablo Picasso lived and worked through one of the great calamities of humankind, and the curator’s display of his War Years sculptures exemplifies the artist’s perseverance, resistance, and will to break from the bonds of tragedy to chronicle history through emotionally captivating art. Holistically, the show conveys the complete spectrum of human emotion—from the bouncy, haphazard assemblage of Picasso’s 1929 Woman in a Garden to the hulking and haunting metal, clay, and bronze Man with a Lamb of the War Years. The curators display each piece of the exhibit with the same attention to detail, but Gallery 7 is especially powerful in its unbridled depiction of humanity’s most passionate emotions: anger, despair, and sorrow.

– Yowana Wamala, NY Arts