Noah Becker’s first solo exhibition in New York since 1999 will open at the Lodge Gallery on November 7th, 2013 from 7 to 9pm. Many of the works were generated in the last two years out of his studio in Brooklyn. They break the seal of white noise haunting the Lower East Side, where exaltation of the new is liable to cheapen the art-viewing experience. One might classify Becker’s recent works as ‘art about art,’ incorporating nods to masters like Dirk Bouts, Pisanello, and Mary Beale. The influence of modern marvels, including Lucien Freud and Andy Warhol, contribute to the mutated output Becker deems “conceptual abstraction.” He places himself within several canons of art history immediately—a challenge to the formulas of collectibility. Becker’s aesthetic preoccupation brings to mind a feisty Chihuahua nipping at the tail of a Rottweiler that refuses to stop barking quotes from Walter Benjamin, gets all life updates from ArtFCity, and refuses to be walked above 14th Street (yes, the modern pup). Like garlic, his style emerges only after being scorched, submitting to the immediacy of his influences in an attempt to transcend them.

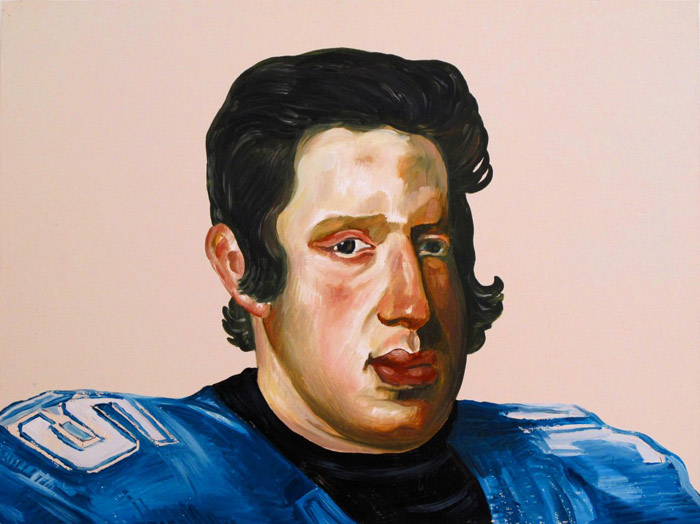

The series of portraits is immediately penetrable, familiar as a vanilla-spiced candle. Neutral backgrounds heighten the artificiality of each sitter’s features. They become clowns, theater actors damned to wear stage makeup in reality like a badge of honor. Nearly all of the portraits are modeled from found images of British hair models from the 1970s. They are cooly shy and demure, with wayward eyes indicating that they had somewhere to be ten minutes ago. These neutral figures meld seamlessly with more recognizable faces—remnants of Diego Velazquez’s portrait of Philip IV in a Tim Tebow jersey, and Frank O’Hara’s doppelgänger, for example. The garb of each sitter is rendered loosely, for the most part refusing to assign an identity beyond facial expression. The portraits are like anemones on a coral reef. By way of their uniformity—their predominantly neutral backgrounds, skewed cropping, and lack of racial diversity—one can acknowledge Becker’s gestural instinct and his kill-tactics. Each character embodies a physical flirtation with decoration. Curly-cues and waterfall locks are rendered in spaghetti lines. The femmes are mysteriously seductive; the men have the pink complexion of an explosive adolescent caging his rage. Decorative elements become details, the only recognizable aspects of the sitters. They feel a bit naughty, even scandalous, in their inability to express a clear backstory. These works are indulgent. Becker claims he acquired “liberation in work that is about nothing.” Like Warhol’s Screen Tests, they rely on atmosphere rather than idea or intention.

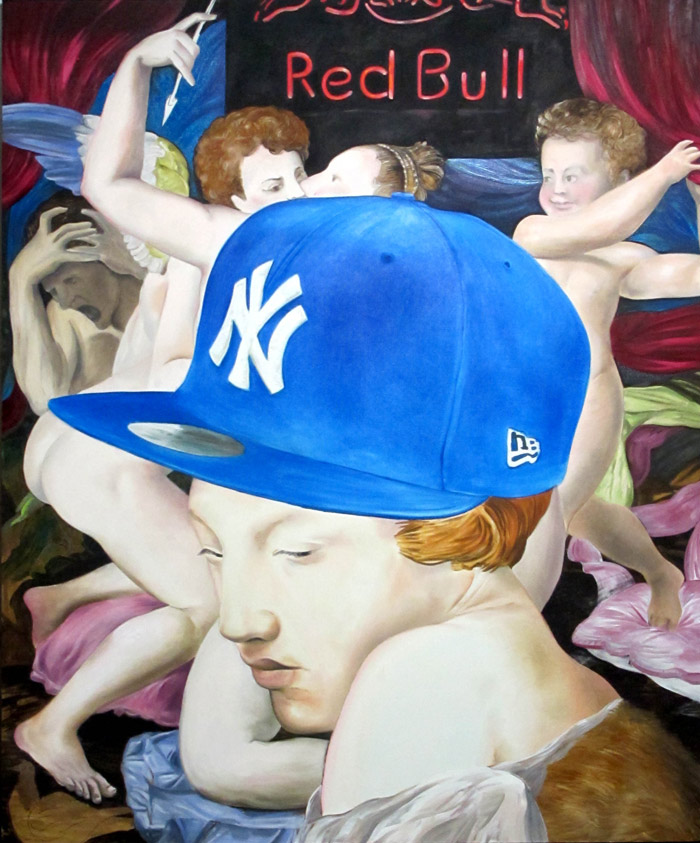

The newest works from 2013 battle Becker’s notion that “people are only interested in something that’s famous.” His aggressive injection of art historical talking points is transparent. The characteristic embellishment of the portraits is swapped for art-historical canoodling. Your Google search for Bronzino or Gérôme will now summon Becker despite the centuries between them. These new works are collaged images, spurned from quick, impulsive concoctions that zap Becker like a neurotic tick. In comparison to the viscosity of the floating heads, this series is more self-aware. Borrowed elements are rendered in perfect detail, allowing the visible gesture or physical indication of an idea’s extraction to go undetected. Becker’s own portrait peaks into the frame of Basquiat’s Charles the First, existing with the work in real-time or seemingly pasted onto the canvas like a window applique. The exteriors, often inflated by advertisements in a nod to reality, are bland boiled brussels sprouts. This intermingling of styles and ideals evinces perspectival confusion, no doubt. Despite the composition’s absurdities, the features of his subjects retain meticulous detail. Like looking for a Sacajawea dollar at the bottom of the piggy bank, these works allude to a treasure that won’t surface. Originality from centuries past is obscured, layered, and swaddled to produce a novel comment on worth.

Is Becker’s offering, arguably unoriginal yet completely consuming, propaganda? By challenging the power of association, he uploads his work into conscious memory and links to legends. He holds the strings like a puppeteer and refuses to rely on simple illustration. Contemporary art’s obsession with the new has the power to short-circuit the visual experience; the trend of resorting to an untapped technique without considering the visceral reaction is irresponsible. Remember, kids, new does not imply good. Becker refers to this phenomenon as the “cultural cringe” caused by “historical paranoia” that everything has been done before. A counterpoint is the market’s adoration of aged works, of the consistent Macintosh apple that draws you return to the orchard year after year. In his refusal to invent for the sake of being new, he appropriates these older references and separates them from their original intentions of wrangling perspective, realism, truth, or physicality. The work has an innately befuddling seriousness to it, yet manages to laugh at itself without condescension. Becker fluctuates between conceptual provocation and a practice very much based in reality. He is wholly embracing the preoccupations he currently has as an artist: what makes an artwork valuable or collectible? When does contemporary begin or end? Oh, the subjectivity of it all! This fluctuation between mortal and deified, derivative and utterly bizarre, suggests a practice that will embrace alterations in hindsight as ripples arise in his reflecting pool.

By Lynn Maliszewski