Russell Tyler’s Solo show at DCKT in the LES returns back in the direction of bad painting but stops midway at a comfortable apex. He has come a long way since I first saw his work at Freight and Volume in 2010. I remember clearly thinking about Kim Dorland when I saw Tyler’s paintings at that time. Now a whole four years later, the work has chilled out. In the last year he has been making thickly painted geometric gradient paintings. In contrast with recent work I’ve seen at Brian Morris and Denny Gallery, the paintings at DCKT are refreshingly more “off” and harder to look at—yes, this is good.

The five largest paintings on the South wall of the gallery do read like screens as explained in the press release, “influenced by crude digital landscapes of outdated 8-bit graphics”. The thick paint and occasional drips echo the grittiness of early Technicolor animation. The gradients are reminiscent of early computer generated advertisements and early arcade game backgrounds. But I also think about old Japanese prints or the rainbow rolls of 1960’s/70’s rock posters.

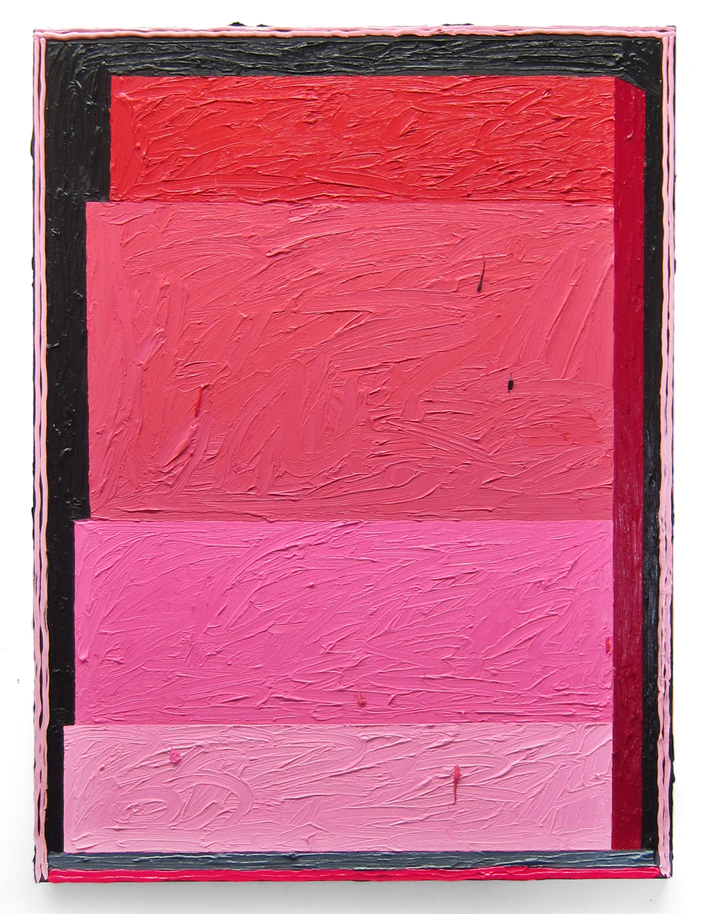

The reductive compositions do remain graph-like but are not so considered. They avoid a lean towards early modernists like Kandinsky or Mondrian, No Golden Ratios make an appearance here. The paintings hover somewhere between graphic color charts and actual thought-out pictures. I do not imagine Russell in his studio staring at this work thoughtfully, or calculating color theory, conceptual, or even emotional content. This attitude matches Russell’s sincere, yet not pretentious personality. He’s no Albers and no Picasso—and I’m glad.

Despite what it says in the DCKT press release about his influence of the screen and early Sci-Fi films, he makes the paintings for themselves—they reference themselves, and I think more about how they relate to his older body of work than any conceptual framework or nod to pop or art history. These are paintings made by a painter who knows how to make a bad painting. And he probably knows how to make a good painting too (I’m talking about formulas). This new work is neither trying too hard or too little. A middle ground rarely tread upon these days. I feel like most shows I see are either heavy-handed new casualist or over-produced craft fairs/flea markets. But Tyler’s new paintings are at a mature point, curbed back from the cusp of beautiful, while not sunken into a shit-show of muddiness.

Most of the time when you see an artist’s body of work or even more than one painting together you began to see relationships and hear conversations between the works. That is hard to do with Tyler’s paintings—maybe because the imagery is simple and similar, but also because the designs are soft and ambiguous. They are open-ended, acting like backdrops, jumping off points or fading dreamscapes. He makes the paintings bright yet muted, geometric yet sloppy. This seeming confliction allows one to read each painting individually, even when they are in a large group and in close proximity to each other. The paintings need to be seen in person—like a Brice Marden or a Julie Torres.

The paint is thick, and vivid, and lush—probably not yet dry. The works smell like oil paint but I still see and read them like graphic, flat compositions. All these other elements are there but don’t get in the way of the literal or implied image. Tyler still retains the remnants of his older style of messy, bad painting. All the paintings at DCKT except the tondo works have double line borders made by squeezing paint directly out of the tube. He does not use this technique as a statement of immediacy. The painted borders act like modernist frames.

Since the entire surface is thick paint brushed on like cake frosting, we see the final image as a field. When one mutation multiplies and becomes dominant, then it becomes the norm. Russell Tyler fills his paintings with flatness.

By Mark Sengbusch