Leah Oates: How did you become an artist and what is your family background?

Greg Sholette: To be honest, growing up outside Philadelphia watching Jacques Cousteau specials on television, my real childhood ambition was to become a marine biologist not an artist. You know, slip on a wetsuit, jump in a submersible, discover new types of sharks and crustaceans.

LO: And?

GS: All that was before my unhappy encounter with higher mathematics. We didn’t get along. Science was out. But my parents were. Though neither professionals nor academics (my dad sold automobile insurance for a living) I was encouraged to explore my obsession with drawing and making things out of cardboard to play with. Around age six they managed to set aside some money to send me to weekly art classes with a local watercolorist named Jeanne Doan Burford (who in fact just turned ninety).

I think its worth noting, Leah that I really don’t think before starting these lessons I was consciously making “art.” I mean drawing and so forth seemed more like a half-magical, half-megalomaniacal ritual or tool with which to manage, or escape the big, sometimes intimidating world of adults. Jeanne began to channel this intensity, focusing it with such classical exercises as collage, illustration, color mixing and the like. She effectively opened-up to me the possibility of my becoming an “artist,” something that my family background would have probably foreclosed as a serious option.

LO: Why do you say that?

GS: Because so much depends on seeing oneself succeed in a particular role don’t you think Leah, and there were simply no role models to follow. None within reach so to speak.

LO: But this was also what, the mid-1960s, there must have been other influences on you as well?

GS: Yes, and as clichéd as it sounds radical change was filling the air it seemed in those days. Nor was it lost on me. In 1970 I was caught stuffing student lockers at my Junior High school with an anonymous “underground” newspaper that my friends and I printed on a mimeograph machine, then state of the art reproduction technology. Bluish-green and terribly naive, the cover showed Mickey Mouse raising a clenched fist to decry the war in Vietnam, imperialist “Amerika,” and police brutality in nearby Philadelphia. I believe we also reviewed LPs by Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin.

LO: How did other students respond to this?

GS: I don’t recall any of our twelve to thirteen year old peers showing much interest in our paper, our politics, or the music we recommended. We on the other hand smoked pot, listened to protest rock, and worried about being drafted some five or six years down the road. I also can’t recall being invited to many parties.

LO: When did you actually realize you were going to be an “artist?”

GS: Not until about 1976 I think when I attended Bucks County Community College in Pennsylvania. There I met the artist Charlotte Schatz who was a brilliant teacher. She pretty much figured me out. She helped me get into The Cooper Union and once in New York my previous political leanings found an ally and mentor in professor Hans Haacke. But I also took some memorable classes with Louise Bourgeois, filmmaker Robert Breer, and art historian Dore Ashton.

LO: And after that?

GS: Well, after graduating in 1979 I became involved with the artists’ collective called PAD/D or Political Art Documentation/Distribution, which was co-organized with Lucy R. Lippard among others. About a decade later I co-founded the group REPOhistory with another gang of artists, educators and activists including Jim Costanzo (AKA Aaron Burr Society today), Tom Klem, Lisa Maya Knauer, Todd Ayoung, Lisa Prown, and Neill Bogan and among others.

LO: What does REPOhistory mean and what did you do?

GS: The name is a spin on the 1984 indy film Repo Man with Harry Dean Stanton, but our objective was to “repossess” lost or forgotten or suppressed histories of working people, women, minorities, radicals and then mark these in public spaces around New York City.

In 1992 we managed to get City permission (under Mayor David Dinkins) to install dozens of temporary, metal street signs around lower Manhattan revealing such things as the location of the first slave market on Wall Street, the shape of the pre-Columbian island coast line, Nelson Mandela’s historic visit to New York just two years earlier, and the offices of a famous 19th century abortionist named Madame Restell—once located where the Twin Towers also once stood. One side of each sign had an image. The other told the story.

LO: So you collaborated making art projects for quite a few years?

GS: Yes, but I continued to make my own work all along as well: wall pieces, dioramas, photo-based bas-reliefs.

LO: But how do these public, collective practices you’re your own art making overlap and inform each other?

GS: In retrospect I think my individual art making has functioned as a sort of refuge for experimentation that in turn feeds back into my more public practices, writings, teaching and so forth. For example REPOhistory was founded in 1989 with a sizable group of other people. However, my interest in exploring alternative ways to represent history had already found expression earlier that year in a nine-foot wide panoramic-collage entitled “Massacre of Innocence” about the death of children in historical battle zones. One year before that I produced a three-part photo-relief piece entitled “Men Making History/Making War:1954” about the politics of the McCarthy era. More of this work can be found on the back pages here.

LO: And this cross-pollination continues today?

GS: Sure, something similar is happening today, for example with my book “Dark Matter” whose themes about history, archives, and resistance reappear in my graphic novel “Double City” that is still in progress. I supposed this is why I prefer to describe what I do as an expanded art practice rather than calling it post-studio, or relational aesthetic, or even social practice art. Besides, as you know I like to make “things.”

LO: But when did you become a teacher?

GS: Short version is that during the mid-1980s I also tried to run a business. It was a prop and model-making shop located in the Gowanus area. The techniques I still use in some of my art stem from this venture, which, shortly after the financial crash of 1987 collapsed along with the local advertising industry. I decided to get my MFA. Heading west I attended the University of California in San Diego where, between 1992 and 1995, I worked primarily with French new wave filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin. No, I wasn’t making films (though I taught film theory), I was instead creating installations and sculpture influenced by cinema. After that I returned to New York as a critical theory fellow in the Whitney Independent Studies Program (ISP) where Benjamin Buchloh, Mary Kelly, and Ron Clark encouraged me to write about the kind of collective, political art of PAD/D and REPOhistory. It was excellent advice. But even with all this education and experience finding a teaching position took a long time to land. Its even harder today.

LO: Do you think the art world has gotten out of hand in terms of money and class elitism? Would it be better to go back to the good ol days of Max’s Kansas City and Warhol’s Factory?

GS: Those particular good ol’ days were somewhat before my time Leah, though I did arrive here as the East Village scene unfolded in the 1980s. Young artists showed their work in galleries like Nature Morte and Fun Gallery and also at various clubs including the Palladium, Danceteria, and Pyramid. Some even sought to reenact aspects of a 1960s SoHo they had only read about in magazines including Warhol’s Factory. In general East Village art was a compilation of campy gestures, or perhaps campiness to the second power, and its ironic self-consciousness dovetailed neatly with dominant versions of post-modernist theory.

LO: Where did you fit into this “scene” then?

GS: Yeah, well my outlook, as well as that of my friends and collaborators, was pretty skeptical. PAD/D for instance produced a critical parody of the East Village art scene in 1984. We claimed to open up four “new” galleries showing anti-gentrification art. In reality these exhibition spaces were just boarded up buildings on street corners east of Second Avenue. We named them “Discount Salon,” “Another Gallery,” and the “Guggenheim Downtown.” For several weeks that summer a group of about eight wheat-pasted posters denouncing real-estate speculators and spray-painted stencils calling on our peers to fight the displacement of low-income residents.

LO: Artists fighting gentrification? Did it work, did you reach your audience with the message?

GS: Yes, and no. But one way or the other our ersatz art venues and the actual galleries they satirized were soon enough replaced by trendy restaurants and boutiques.

LO: So things have really changed for the worse?

GS: Also yes and no. I mean maybe the feeling today that the art world has been swallowed by hedge fund operators, global real estate tycoons, and finance capital is not entirely new, no, but you could also say it is really like the 1980s art scene turned up full volume.

LO: That seems pretty bleak, no?

GS: Thankfully there is still push-back by artists and their allies. I am thinking of Groups like Temporary Services, Aaron Burr Society, Chto Delat, and Pussy Riot and many others who continue to do the kind of resistance PAD/D and REPOhistory were engaged in today, just as PAD/D and REPOhistory were continuing to do the work of Art Workers’ Coalition, Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, and Angry Arts and other groups that came before them.

LO: What about your own work? You might best be described as a conceptual artist and a political activist, writer, curator and educator, yes?

GS: Conceptual Art? Right because of my association with Haacke, Gorin, Lippard and the ISP of course this aligns me with this legacy. I guess that is true in a way.

LO: Correct, though?

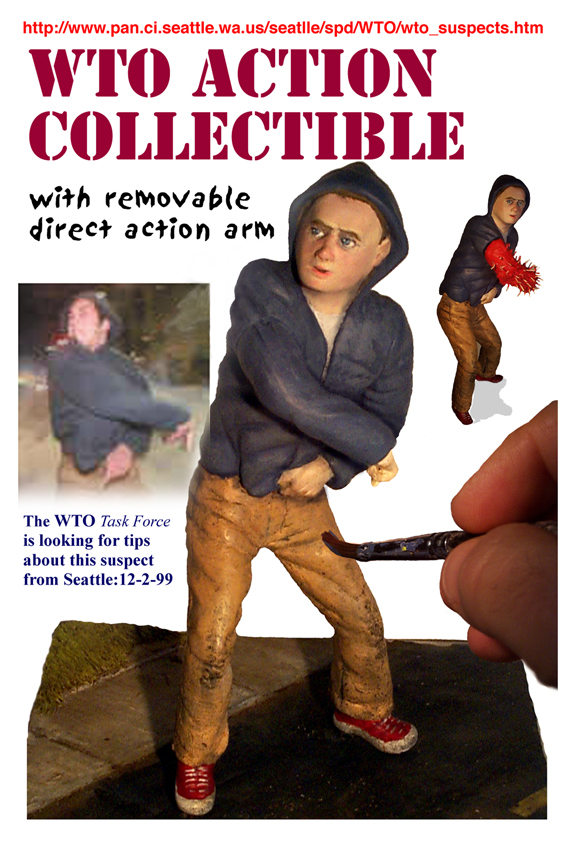

GS: It’s an honor to have my art connected to theirs. Then again, labels are hard to make peace with (as much as they are impossible to live without). So yes, while I do try to maintain a theoretically informed practice at the same time my work does not look like “conceptual art.” In fact it often seems just the opposite: hand made, figurative, with low-brow, pop-cultural references. Sometimes my art even comes off as conspicuously “rearguard.” I mean, over the years my projects have made use of an odd assortment of things such as artificial plants, diorama techniques, comic book imagery, miniature tableau, and sculpted action figures in order to present narratives about history, class, and political injustice.

LO: So what is your working process like?

GS: Hard to describe, but I just finished David Joselit’s recent book “After Art,” and thought for a while I had the answer. Joselit starts off discussing the far too many images that are constantly coming at us from the Internet, advertising, cinema, TV, etc… And then he counter-intuitively argues that “art” is not getting lost in this image-blizzard. Instead it has become a powerful generator of what he calls format. What is format? He explains that if traditional artistic mediums lead to object making, then format establishes patterns that create links and connections across images and long threads of content. The format therefore, is how an artist re-uses images, or ideas in order to produce a work. One of his favorite examples is Pierre Huyghe whose art always changes form, but there is a range of ideas lurking behind each piece. So After Art is when artists stop making discrete “works” and instead reiterate and comment on existing materials, sort of like recycling with a mission.

LO: I can see a certain connection to what you do Greg.

GS: Me too. But then when I finished After Art and really thought about it I realized that if Joselit’s concept is correct, then my work suffers from format failure! I mean he subordinates mediums, materials and content to his morphing paradigm. But I still retain a relationship with all three in my “expanded” practice. When I make art, or when I write a text for that matter, I find that I am assailed by the specific concrete nature of form and content.

LO: Please Explain.

GS: Lets say I am trying to write about the concept of the archive. Despite every attempt to discuss it conceptually, I know sooner or later that I will be forced to dip down into the archive’s specificity: its sprawling mass of missing practices, lost details, and dog-eared documents. Its as if some archive-agency commanded attention from below. And this dusty dark matter force tears up holes in smooth surfaces and turns abstraction pathological.

LO: A conceptualist!

GS: Ok, why not. Because what has shaped my art and its working process is less some profound inner drive to become an “artist” (although I admit I am as attached to that romantic idea as anyone) and is much more like the result of a string of fortunate encounters involving certain individuals and groups, certain institutions and historical moments, even certain objects and materials. As much as I would like to claim I am in full command of this process it’s a collaboration of sorts, a collaboration with the past –thus my interest in archives and history– as much as it is with the future expectations of a more egalitarian society. So that when all is said and done “art” is for me at least the way we think thought in material, plastic terms, but also reciprocally, it is how certain events, ideas, hopes and encounters become thinkable to us. And it’s a process that sort of bypasses our best attempts at exercising total authority or control over it.

LO: What are your upcoming projects?

GS: I am currently working on a new iteration of Imaginary Archive (http://www.gregorysholette.com/?page_id=587) for Kiev Ukraine this Spring, which, given the situation there should prove pretty compelling. I am also continuing to add chapters to my graphic novel Double City, and I am especially looking forward to the solo exhibition of new work I am preparing for Station Independent Projects in the Fall.

LO: What advice would you give an artist who has just arrived in NYC and who is not sure where to begin?

GS: Do your research. Seek out like-minded people. Map out the terrain. Stay tough.