Benoit Mandelbrot, the father of Chaos Theory, in his unfinished memoir told the story of when, during the early 1960s, he walked past a classroom at Harvard University and noticed a fellow-professor drawing a near-identical diagram to the one he’d recently landed upon in the course of his groundbreaking research. Possessive of his discovery, Mandelbrot burst into the room, interrupting the lecture and demanding to know where the economics professor got this information, to which his esteemed colleague replied: “I have no idea what you’re talking about—this diagram concerns cotton prices!”

Ironically, what Mandelbrot saw that day merely confirmed his notion that chaos and order are two sides of the same coin. Similarly, artist John O’Connor, whose latest show recently opened at Pierogi Gallery, seems aware that his quasi-scientific works are imbued with a hidden pattern.

By approaching everyday phenomena like the lottery; meta-dieting, computer-generated conversations and psychopathic traits, the artist has managed to unlock something of a veiled thread that shows humans to be simultaneously rational, superstitious, and abundantly absurd. Moreover, The Machine and the Ghost evokes a deep sense of alienation at O’Connor’s core.

Works in this show fit neither traditional science nor machine-like concision, but rather a hand-made aesthetic that is imprecise, but never sloppy. The artist begins each composition with an equation entirely of his own making, charting coordinates based in point, line, shape and color. When fully mapped out, they generate strange optical patterns which seem to confirm a secret knowledge at the heart of the mundane.

Take Self Portrait with Sunspots for example. The composite features a series of nine framed pictures of the artist’s face with photonegative captures of the sun’s daily spots superimposed over his skin. A subtle politic might be that the sunspots look like legions in this context. Though more interesting, perhaps, is the raw emotional content behind O’Connor’s various hairstyles here. A mussed tousle one day, an almost violently-shaved stubble the next, and a complete cover-up with ski cap by the end. It is as if the artist’s identity crisis somehow coheres with the ecstasy and agony of the sun’s harsh unpredictability.

The Shape of War, one of three sculptures in the show, operates less like traditional sculpture and more like a diorama that one could imagine Copernicus constructing in his laboratory as a means of measuring some new hypothesis. The hand-drawn texts and jagged shapes here are merely plotted based on a system set up long before the aesthetics emerge. Any onerous thoughts concerning the topic of war practically disappear, as the suspended sculpture’s framework appears both impersonal and utterly weightless.

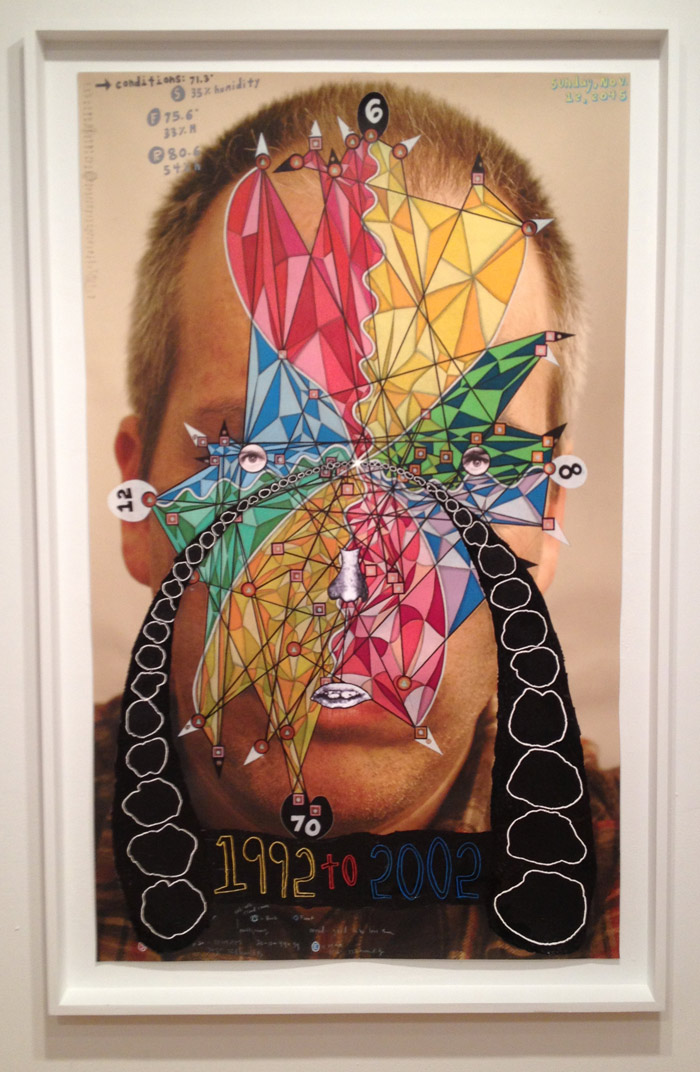

Monster, 1992-2002 is a large-scale facial photograph collaged over with what looks like a rainbow-colored spider web masking the artist’s face. Basing the color and pattern on a pre-set equation where a sub-70°F day is plotted red and a plus-85° day is green, the work clearly acknowledges the human subservience of mood-to-weather conditions. Yet, never obvious, the Kafka-esque monstrosity that O’Connor’s face metamorphoses into becomes strangely moving, its beauty a kind of impassioned loneliness that easily disturbs.

Conversely, Portrait of a Psychopath, the show’s largest composition, is sobering to its very core. In the center, a psychedelic green, pink, and yellow mountain emerges from the plotted coordinates that match lists of figures like Odysseus, Pol Pot, and Ronald Reagan on the right, against a series of phrases to the left side such as, “Warlike courage far above norm” and, “Skill at faking emotions including love, sincerity, and regret.” The sheer verticality of the mountain gives it a monumental feel amidst the rest of the show, and a neo-liberal interpretation may be fully in line with its op-art construct. Yet there remains a shocking element here that defies politics. For surely one could expect a contemporary work based in war and corruption to have something of a mannerist irrationality. Yet, the way the composition remains resolutely composed is perhaps its most disturbing and lasting quality. Instead of pointing fingers, O’Connor seems to suggest that given the same power, each of us could become such a monster.

A 75”x60” work titled Butterfly is almost too much to grasp in one viewing. It is a text painting, but not the usual spatial affair the genre seems to imply. O’Connor instead stacks a dizzying array of hand-drawn sentences punctuated by brand logos which he employs in the telling of a single day begun by chasing an Ambien capsule with a bottle of Budweiser.

The narrator (whom we assume is O’Connor) then heads off to the Truth Gentleman’s Club where, in an extreme burst of physical and mental energy, there are several fast-food pit-stops, more prescription drug intake (Prozac, Ativan), an attempted mugging and finally, overwhelmingly, a great crash unto sleep. The viewer is left to wonder whether any of it really happened or if it was entirely dreamed. As such, the yarn becomes something of a waking nightmare, whose surrealist tropes blend uneasily with the barrage of consumer products to create a composite that is unapologetically neurotic.

In the end, the great strength of The Machine and the Ghost remains its utter lack of artificiality, despite the detached nature of its equations and the strange biomorphic patterns they produce. That such visual chaos can be both breathtakingly beautiful and endlessly hypnotic makes a very solid argument for the most basic act of stepping back from life’s messy details as a means of reinstating order and civility.

By Brian Chidester