Mark Sengbusch is a painter, curator, and Sudoku Master living in New York City. Jeffrey Scott Mathews is a painter, writer and musician based in Brooklyn. They met in Detroit, in 1997 at College for Creative Studies. They later studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art where they picked up on a dialogue that will carry on in perpetuity.

JSM: You and I have had a continuous and lasting dialogue regarding abstraction. In preparing for this piece we reminisced over a particular quote from Azerbaijani crystallographer Khudu Mamedov where he asserts:

Townsfolk= geometric surroundings / natural art

Nomads= natural surroundings / geometric art

Could you elaborate on how you view this phenomenon in relation to your own work?

MS: You told me about this essay like 6 years ago and it’s always in the back of my head, especially when I travel. (I notice my dreams change when I travel, too). I moved from MI to NYC in 2008. As in Mamedov’s theory, I ended up making gestural, natural art while surrounded by the pattern and geometry of the Big Apple. The result was the Strata Paintings. (See Central Wave Strata, 2010) Very loose, colorful, organic, detailed. Strata as in layers – sediment. That Simpsons cut scene of the layers of earth under their house with dinosaur bones, etc and that poster from High school of the different eons, like layers of a cake, upwards from bacteria to fish to dinosaurs to mammals. Perhaps this phenomenon Mamedov posits can be explained as easily as a longing for what one has not.

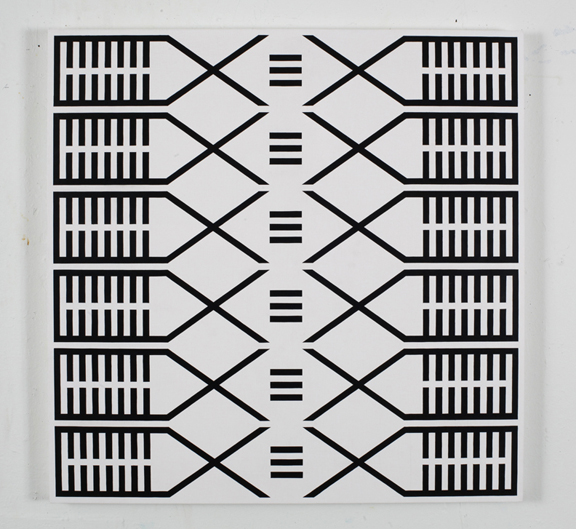

In January of 2011, I was at Vermont Studio Center for two months. I went with no plan as to what kind of work I’d make. I made the Comb paintings (See Whorl Stasis, 2011). Loosely based, (and for reference sake), on Ancient African Combs and tools. Could I have been subconsciously summoning the skyscrapers of New York 350 miles away? I wasn’t thinking about buildings and highways while I was in the small, old mining town of Johnson, Vermont. I had a studio visit with Katherine Bradford (or maybe it was Carrie Moyer) and upon telling her about combs, blueprints, and NES she said, “Why do they have to have a real-world reference?” I thought “Bitch…she’s so fucking right.”

Then it hit me. It was there the whole time: overhead view vs. normal horizontal or human view. Scale and scale shift, what is the map and what is the idea of the place? Viewing the painting like an Island or a window? In other words – division of space; positive/negative push-pull, no overlapping, no layers.

In hindsight it seems too perfect. That I would make the Organic “Strata” painting in the city and make the Structural “Comb” paintings in the country. Maybe just a coincidence, but I think Mamedov was on to something. I haven’t totally figured it out yet.

JSM: One could view the phenomenon of inverse as tying into the debate of existentialism (finding meaning through making) vs. structuralism (reducing meaning or relationships through editing/structuring). Do you see yourself as an Existentialist or a Reductive Structuralist?

MS: I guess the latter – Reductive Structuralist. I consider all the work I make to be more about “the idea” or “feeling” of something rather than that thing (itself) as an endpoint or finale. (i.e. the idea of early language/design and not a specific re-creation or re-interpretation of say, the Rosetta Stone or Hamarabi’s Code).

Last week Katherine Bradford told me a quote by painter Suzan Frecon, “My decisions are visual.” That is poetry – damn. The ultimate epitome of a simple, honest, ideal artists statement. I told K-Brad immediately, “Imma steal that!” It goes back to a term I bit off of you many years ago, Jeff. You mentioned a “Non-circuitous” way of making art. I dig it.

We don’t make art in a cave, of course, far from it. We went to grad school and we live in NYC. But I try and steer clear of the tentacles of art history and contemporary trends. So, by allowing a natural puree to waft through me and into the paintings, I create as close to an objective product as possible. I avoid becoming immersed into/blinded by the objectifying gaze, thus becoming the player and the critic.

Back to reducing meaning by editing/structuring, I make between 50-200 drawings for each Comb painting. Making the drawings and editing them down make up 1/3 of the whole process (but is really the only creative part!). My criteria in editing is 3 fold (loosely):

1. Too Op-Art-y

2. Too design-y (rugs, etc)

3. Too busy (i.e. more than one to two cornerstone elements before reaching full circle to a field)

By choosing the drawing that lacks 1-3, the final painting exists in limbo. No affiliation to known scale, orientation, or basic design shticks – intentionally anonymous. It’s like Superman losing the race or Goku losing to Mr. Satan. “The stone that the builders refuse will become the cornerstone.”

JSM: In ANTI-OEDIPUS Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guatarri postulate that a schizophrenic out for a walk is better than a neurotic on an analyst’s couch. I am taking this to mean that breaking structure is a better solution than trying to find it thorough analysis. In relation to your work, I wonder if you feel that the process of making is your schizoid walk, or if it is commanding the importance of rigidity of form? Rational or Anti-Rational? Perhaps this is the ultimate painters paradox – synthesizing the rational (paint, alchemy, spectral composition) with the non-rational (the mystical, spiritual, or spectral walk.)

MS: Fuck you, Jeff! That’s like 5 questions in one! And you’ve only given me A or B options, yo! Remember, my decisions are visual. Paint is paint AND language. I try to simplify shape and line to its most base form.

When was visual communication born? Did “design” exist before? Could the first written communication have pre-dated Sumer, a land cloaked by design? Was the zig-zag line just a frivolous, decorative, subconscious mark on a pot? Was it strategically, naturally, or instinctually decided to be a zig-zag line representing mountains as opposed to parallel horizontal lines, which would have signified desert plains?

I think about these things – but not in my studio. Yes, my schizoid walk is stumbling backwards to a time/feeling/state of mind before written language.

JSM: Could you talk about language in relation to your work? I recall we shared an interest in Lewis Carrol’s Symbolic Logic.

MS: Yes, there is a logic to the work, way more in the new Kuba Comb paintings, though. Raffia or Kuba cloths are ceremonial textiles from the Congo, worn as ceremonial skirts and at times used as currency. You put it on the floor, wear it, hang it on the wall! It’s a hard but natural balance for me but I think about the diversity in perception of things like Kuba cloths. When I draw, the line creates a thing and a place. It is also a re-presentation or illustration of that thing – and a map of that place. One may think, “Hey, but it’s really only the latter” or, “You’re only a sculptor”. But no – especially when it becomes a painting (from the drawing), the line width is what it is: A = A.

When I was a kid I loved making mazes. Of course, in the back of my mind it was a map of some sort, but not really. It wasn’t make-believe. I was invested in the real thing – pen on paper. Maybe that’s the ultimate trickery of design; that you cannot ever fully remove the signifier from the sign.

JSM: Considering solitude, have you ever had a conversation with yourself? Who was doing the asking and who was answering?

MS: Not sure. But, recently I was at Alicia Gibson’s studio and Yasamin Keshtkar queried, “who is the speaker of text in a painting?” Like who is the maker and why did she make/say this? Or is it a story and the speaker is different than the maker? When one reads text, whether in a zine or on a painting, who is speaking? Is it in first, second, or third person? This conversation made me think about who is the “speaker” of my paintings or images in my paintings. I guess I like to leave that ambiguous. If you’re hunting for arrowheads – it’s hard to know if it’s just a freakin’ rock or an authentic man-made object. That is the ever quiet and rhetorical conversation between “I” as a maker of things and “I” as storyteller, historian, or magician.

JSM: How do you view the concept of time in relation to the concrete materiality of painting?

MS: When we met in Detroit in undergrad I walked into the dorm room behind mine in the smoking back tower of the ACB building. You, Ted, Kobie, and the gang were playing Rampart on the NES. In Rampart, you build your castle (overhead view like a map or a drawing) and you bomb your enemy’s castle, he bombs yours – then you rebuild. This destruction/creation was like a time-lapse.

I see my paintings like this, kinda; a scale model or a blueprint is a re-presentation. I can pick it up and feel it – so it becomes some thing, not an idea.

I made a mouse maze out of two by fours when I was a kid. This was real, not a scale model. English garden mazes, corn mazes, etc. can be experienced from an objective view as in the map or the mouse maze, or as a participant such as in a corn maze. Video games have given these things names: First person shooters, overhead-view God games, etc. So yes, I consider the element of time inherent in my work. There are different stages in the life of a thing. First, it is not there, then it is there. It exists, then it maybe changes, it fades or crumbles or grows, and eventually all things disappear and are again “not there”.

JSM: Could you name the three of your least influential painters?

MS: Peter Halley, Matthew Ritchie, Francis Bacon.