Leah Oates: How did you become an artist and what is your family background?

Carol Salmanson: I come from a family with a humble background and ambitious parents, who had no interest in the arts. I was passionate about both visual art and ballet, but my mother actively discouraged me until I was in high school, which is when she gave up. Still, I took her feelings to heart and stopped doing anything related to the arts at the age of 20. Therefore I got my degree in biological psychology from Carnegie-Mellon University. I subsequently got an MBA from the University of Chicago, where I developed a severe allergy to the theoretical approach to things.

I resumed in the arts a few years later when I started taking ballet classes while living in Denver, where I was renovating houses. When a knee surgery prevented me from dancing, I signed up for a drawing class. I was immediately reabsorbed, and the instructor said that I should be “doing this full-time.” That was all I needed to hear.

I then moved to New York and started studying drawing and painting at the Art Students League, as well as studying art history on my own. I elected not to get an MFA because I thought it was strange to be judged proficient in an art form, and I couldn’t stand the thought of any more theory.

LO: What are the ideas in your work and what is your working process?

CS: I started out as a painter, depicting abstractions with representational components that were concerned with movement and space. There was always some form of depth and space in them. My first mature work, a series of paintings entitled Architectural Gems, were jewel-like geometric constructions with gold edges, almost like cloisonné. They have a lot in common with my light installations now. After a certain point they had lost their vitality, and I started painting pulsating objects made of many colors and textures set on colored fields. At first the fields were made of woods stained with rich colors. I then discovered reflective pigments, which offered the possibility of greater depth so that my paintings could move in and out of space. I got especially carried away with interference colors, which look opaque or transparent depending on the angle of light relative to the viewer. They are usually placed over black, but I played with them on different colors instead, so that the backgrounds would change color as the viewer walked around the paintings. I also worked with iridescent grounds, and at one point placed a series in deep open boxes with neon light behind the paintings. The area between the inside of the boxes and the paintings looked like a frame of light. That was my first work with light, and it took me some years to get back to it. I really wanted to continue, but it was difficult to find a place to start—the specter of learning about the behavior of light, the various technologies available, electronics, and fabrication was daunting.

LO:At a certain point you began to create work with light to expand on spatial and color concerns you where exploring in your painting. Please elaborate more on this progression in your work.

CS: Before I got back to making art, I was renovating houses in Denver. I was essentially altering space within a structure, which is what I do now with my installations. Doing renovations while studying dance gave me a strong sense of how I moved through space, and how I responded to it. I was especially happy if I could change the feeling of the house from dark and gloomy to light and expansive. It was thrilling to me that I could completely transform a space using color, texture, light, and scale.

This sense was further developed after I moved to New York. I saw a lot of dance performances in the minimalist era when there were no sets or costumes. The lighting design—especially Jennifer Tipton’s—created the entire theatrical experience spatially, perceptually, and emotionally. When I saw an installation of Robert Irwin’s at Pace that involved light (“1,2,3,4”), I realized that I could do that with visual art as well, and wanted to get back to that sense of space. I couldn’t do that with painting.

You can carve volumes out of light, but it is immaterial so you can move through it. It beams into you, and it also surrounds you. Because of its range of color and scale, it has the capacity to elicit a great range of feelings. The way I work with it I can use the knowledge of color I developed when painting, and can also play with transparency and reflection.

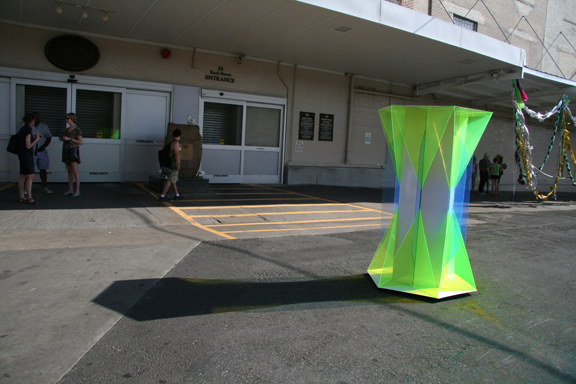

Carol Salmanson, Lot’s Ex-Wife (Pass the Salt), 2013. Fluorescent-edged, plexiglass, prismatic reflective sheeting, steel

48″ W x 72″H x 48″D

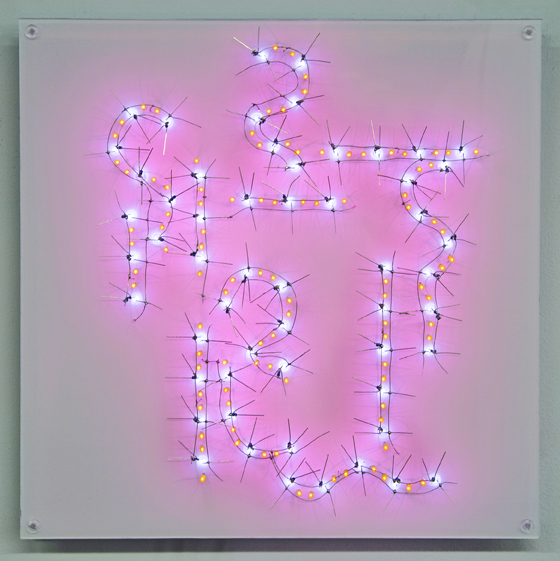

In my installations, I’m responding to the site, so they usually end up using architectural elements. In my small work of the last few years, I’m bringing back the gestural abstraction that was in my paintings, and using the shapes and colors of LEDs to make work that hangs on a wall like a painting or drawing. I am using the wiring as a drawing and the LEDs as paint and form.

LO: Why do you think art is important to people and to the world?

CS: Images, both moving and still, and other kinds of visual stimulation are very important to the way we negotiate the world. We are bombarded with them every day, and people now have a more keenly developed sense to visual stimulation than ever before, even though fine art and art appreciation are rarely taught in schools. Obviously, this is because technology has so rapidly changed the way that we can see everything. But many kinds of fine art are still dependent on physical presence for the viewer to experience its scale and texture, so visual art has a hard time touching as many people as do the art forms that can be easily reproduced and acquired. Art museums are packed, so there is still some kind of human need.

LO: What advice would you give an artist who has just arrived in NYC and who is not sure where to begin?

CS: Get to every museum and every gallery show that he or she can. (Of course, that means that there’s no time left to make art, so maybe no one should listen to me.) And, ignore fear. Or better yet, welcome it because that means that whatever causes it is something he or she should be doing.

LO: Who are your favorite artists and why?

CS: My taste is always changing, and I guess that is due to what I am working on at the time. Right now I am enthralled by the mid-century Constructivists—especially those from South America (such as Lygia Pape, Lygia Clark, Rafael Jesus Soto, and more)—and Soviet concrete architecture. That stuff knocks my socks off, and my recent installation Hercules Lite and my sculpture Lot’s Wife (Pass the Salt) are heavily influenced by these sources. I love that I can use a form similar to a structure made of heavy concrete, but get the opposite effect from transparent and reflective materials.

Still, there are some sources that never change. Byzantine mosaics are my first love. The rich style of their color and imagery always moves me deeply, and the way they are integrated with their architecture and use the light streaming in their windows is awe-inspiring. Persian miniatures are a staple, for the same reason ironically: the way they bend space to communicate depth, and their colors work together to create an effect that I can’t stop looking at once I start. They are so small, and yet to me they feel so big. I also love the theatricality of Robert Irwin. Matisse never disappoints, and I see something different every time. I think it goes without saying that Dan Flavin is…. well, I don’t even know what the right word is for his work.

LO: What are your upcoming projects?

CS: I have a solo show in the fall at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey. Also in the fall, I’ll have my first curatorial endeavor, a show called “The Language of Painting” that includes artists who use color and line without paint. In January, I’ll be doing a window installation as part of Time Equities’ Art in Buildings program.