By Manuel Alejandro Rodríguez Pardo.

The Empire State Building lights up with the colors of twelve of the most iconic artworks of its collection. Michelle Obama and Bill de Blasio cut the ribbon while famous established artists and high end brands such as Audi and Tiffany & Co. contend to be the first in welcoming and congratulating. This May 1st Manhattan celebrates the culmination of the biggest art district in the world.

Marcel Breuer’s building, inaugurated in 1966, is an igneous rock bunker with rough surfaces and

proportions. It is a menacing Cyclops refractory to its architectural environment. Breuer’s design was

coherent with the already anachronic and romantic idea of a Whitney Museum as fortress and shelter

for the American art that was disregarded if not blatantly scorned by the big cultural institutions such as the encyclopedic MET and the Eurocentric MoMA. 2015 Whitney, three miles Southern, and closely flanked by the Hudson River and the High Line Park, is the absolute antithesis of the former building.

Renzo Piano was chosen by the Board of Trustees to make a significant expansion for the museum eight years ago. The Italian architect is specialized in museum spaces and he has built and projected twenty five of them spread around the world. The diaphanous Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the mimetic Menil Collection in Houston, the daring expansions of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Harvard Art Museums, or the Botín Center for the Arts that will hover over the bay waters of the city of Santander in northern Spain this summer.

One would say that Renzo Piano has turned Breuer’s building inside out. Those huge negative echelons of the façade have been turned into large terraces. The stairs have been pulled out, and that volcanic somberness has turned into bright white steel sheets and ample glass surfaces. If Breuer’s building was a bunker, Piano’s building is an open square. Not only because the lobby carries that name but also because the building can be seen through from East to West with no interruption until the horizon. This perspective is particularly possible from the High Line Park. The elevated section of a disused railroad runs parallel to the river from the Javits Center and the Hudson Yards (the pharaonic development that encompasses 16 skyscrapers, the 7 Subway extension, and the Culture Shed, an international center for artistic and cultural innovation where the New York Fashion Week will start taking place in 2018) southwards through Chelsea’s 350 art galleries, until the very gate of the Whitney. The High Line Park attracts five million visits a year, and the museum is ready to receive and even transform them: Because this mille and a half of aerial gardens now have a destination and theme delimitation. There is no other art district so large and dense.

Perhaps this reason suffices to extend, to triple, Whitney’s expositive space, and transform the house of the artists in the “house of the curators” as Chief Curator Donna de Salvo called it recently. Ms. De Salvo and her team of six curators worked closely with Renzo Piano in designing a building where art was first, a functional building projected from the inside out.

Renzo Piano en la inauguración. Photo by: Alejandro Pardo for NY Arts

The inaugural exhibition is naturally the biggest in the museum’s history and fills the space with

artworks from the permanent collection. Jasper Johns’ stacked “Three Flags” (1958) established a

record price for a living artist when the Whitney Museum bought it for $1 million in 1980. Or the

magnificent “Rose” (1958-1966) by Jay DeFeo. Her opus magnum that meant eight years of work for her

and ended up buried alive in a seminar of the San Francisco Art Institute. Willem de Kooning’s “Door to

the River” (1960) that may veiledly refer to the qualities of the West face of the building. Or the

photographic series “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” (1979-96) by Nan Goldin, which is so meaty and tender; and so many others.

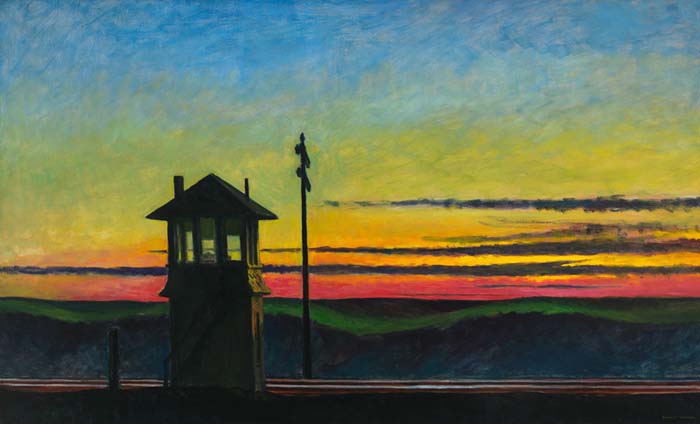

Edward Hopper Railroad Sunset 1929.

Carter E. Foster, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawing of the Whitney, puts the accent on the

central role of Edward Hopper in Whitney’s collection: “One of the first exhibitions he had in his life was

at the Whitney Studio Club, which was the organization that preceded the Whitney Museum, where the

Whitney grew out of. He was supported by the museum: the painting “Early Sunday Morning”, which is

my favorite painting from the whole collection, was bought just a few months after it was painted, so he

felt that support early in his career. He had two retrospectives in his lifetime here at the Whitney, and

he became very friendly with the curator Lloyd Goodrich who then became director of the Whitney. So I

think he felt that the Whitney was his home as an artist. In fact, he left his collection to us when he died,

so we have the largest collection of his work and a long history with him.”

“Early Sunday Morning” was inspired by a building that belonged to this neighborhood. The original title

of that painting was “Seventh Avenue Shops” which were between 16th and 17th Street. And actually

Gansevoor Street, where the Whitney is now, used to extend up to the spot where that building was.

However the painting doesn’t attempt an accurate representation of the building. He painted based on

what he saw, but memory is the subject of his paintings. There is something deeply poetic in the way he paints the memory of the mundane.”

Photo by Alejandro Pardo

The permanent collection of the Whitney Museum has great value because it’s a piece of the art history

of the United States and the world, in so far as its art is universal, and since many of its artists weren’t

born nor dead under stars and stripes. This been said, it’s fair to wonder if the highest value of the

Whitney resides actually in interpreting the past within a clear perspective of the present, and an

unflagging dedication to spur the future. The Whitney Biennial works as a systematic factory of

contemporaneity. The team of curators want to take their time in the searching process and have

postponed the Biennial until 2017, so they have the whole 2016 to enrich our next contemporaneity to

come. Who’d be the next Georgia O’Keeffe, Jackson Pollock and Jeff Koons?