1. Eh, voilà! Inside the commune mailbox is an old fashioned, hefty brown flat packed with books from Antenne Publishing in London. All of them are by or about one Victor Boullet, a migrant artist with a French name, who claims to be of Scottish origin but was brought up in Norway, and is now waving the flag of Paris. Who exactly is Victor Boullet and what is his project? The only sane way to approach the subject is by fiction, in which Victor Boullet is a character. Which, it turns out, is precisely his goal.

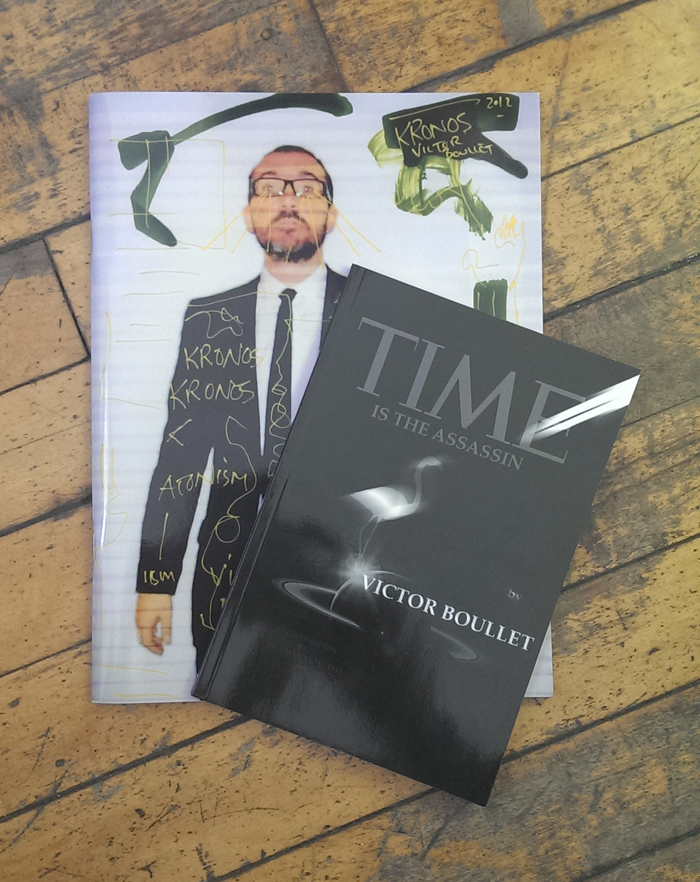

2. The flat has three books: Kronos by said Boullet, a slick and glossy photo tour of the artist’s work circa 2012 (vegetables and beach scenes thrown in haphazardly), The Institute of Social Hypocrisy by Victor Boullet, a massive white tome with photos and text, and Time is the Assassin, which purports to be something like a novel, and which I have been tasked to review. I dismiss Kronos as being yet another artsy exercise in self-justification and note that despite the intriguing title, in Social Hypocrisy much of the text is written by others.

3. Time is The Assassin is the black sheep of the bunch. With more than a hint of anxiety I wonder if this V. Boullet can pull off the ritual exercise in self-justification. Being a literary type, I miss neither the reference to Rimbaud’s Illuminations (the line “Now is the time of the assassins” appears in Matinée d’Ivresse) nor the cheap cut-up of the cover of Henry Miller’s Time of the Assassins. Those two are from another world, prophetic texts, records of the author’s confrontation with himself. Mr. Boullet is setting high standards on which to impale himself.

4. On the largely black cover, Victor Boullet’s name appears in blazing white – in this first five minutes, I’ve already gotten the point that this gentleman likes to bruit his name about—the title is in gray letters and down near the bottom in barely perceptible type, “Ghostwritten by Kristian Skylstad”. Ahem. My sensors quiver wildly. Out come the scapels. I prepare to move in for the kill. Mr. Boullet has his very own ghostwriter to do the work for him.

5. Let me tell you something I didn’t know at the outset of this review, although it should have been obvious from the moment the box was open: this Boullet is a trickster. He is canny, and not without his humors — although he is careful to avoid the comedian’s fate. One example: he invited the curator Damien Airault to a week’s residence at the Institute of Social Hypocrisy’s gallery in the Marais and — held him hostage. Airault could neither leave the gallery space nor communicate with his captor — the artist — for a week. Food was ferried up the side of the building in a basket. A neat role reversal — a curator trapped inside a gallery — as well as a commentary on power relations in the always-ethical art world. “I want to make him a better person, a better curator,” the droll Boullet said by way of explanation.

And now you know more than I did when I took Time Is The Assassin with me into the metro, to ride around for a few hours and read the book twice.

6. The novel takes place in a dreary suburb on the outskirts of Oslo, in a dreary bar that is way closer to Hell than, “fucking, swinging Pennsylvania.” (The author’s words.) The opening pages are exceptionally dubious, a messy, post-modern wank-a-thon. For example? Everywhere:

“There was a time when art could alter society, but that chance was missed. This in front of me, these four imbeciles sitting with me, a hypocrite either way, cannot and will not be changed by art. And these four in an absurd way control society in their passivity and I don’t even know or care if I know or care if that’s OK or if it matters.”

Who is speaking, Victor Boullet or his ghostwriter Skylstad, and who cares? I’m barely to Trocadero and I’m tempted to spin the book out the window at an angle. With a bit of luck there will be a car passing the other way and the book will land on someone else’s lap. That’s part of Boullet’s plan, too.

7. It gets better: people are getting drunk and they make fools of themselves, humanity enters, a possible novel raises its head. There is a cast of characters: Boullet, endlessly pontificating, superior to the others; his brother the photographer, the butt of most of Boullet’s jibes; the occasionally glimpsed Skylstad himself; Tim the Jacuzzidude and Tina, the drunk, who sobers up long enough to deliver a fascinating excursus on what blind people may or may not see. A kind of anti-novel takes shape, in which drunks in the middle of nowhere debate life.

“Maybe I’m blessed with standing in a twilight zone here in the road of Saturn, in pure delight, almost touching delirium… It’s genuine frenzy this, standing here at the bar. I’m consumed with gladness. A taste of heaven. The moment of inspiration, brought to me by intoxication.”

I dodge the cops at Republique and take the No. 11 to Place des fetes.

8. Boullet’s idea is to be a fake, a hypocrite, an actor — while saying something real about the art scene and life. His paintings are bad, his sculptures derivative, and there he is, feeling his way, asking us, “But are we really alive?“ A pest, a nebbish, a loser, like your current NYC mayoral candidate, who, while claiming to be faithful to his wife, cannot keep his grubby fingers away from the naked pix. In Boullet’s case, Art is his wife. It must be everything he wanted when he was a kid, and now he finds the only way to be faithful to the original idea is to drag his bride through the mud.

But with humor. He imprisons curators and forces his empty work which looks good into exhibitions and raw space — and no one can tell the difference from the other stuff on display. When the Institute went bust and Joseph Tang opened a gallery, Boullet created an installation that loaded the space with dim sum noodles which slowly moldered away.

9. Whether it is Boullet’s intention or Skylstad’s, the novel is constantly searching for a way out of our society’s materialism and the trite, platonic otherness festering inside conceptualism. Gilles Deleuze’s A Thousand Plateaus is mentioned at length. Then Shelley’s Defense of Poetry, Anais Nin, and an angelic appearance by Marina Abramovic somewhere in the dark between two bars — surely one of the book’s high points — even if it’s clear that these Grand and Glorious Guardian Spirits won’t get Boullet out of his jam, which is: “What to do now?“ For that you need the supernatural, an extra-human agency. The book delivers it in the form of a talking bear that out-talks Boullet.

Miserable miracle, the book is awkward, excruciating and funny. (Its reflections on Norwegian and Scottish cultures alone will be enough to make the Tourist Boards grind their teeth.) In other words, a night of serious drinking. It is 87 pages long and the best Anti-Novel of the year so far. By anti-novel, I mean a piece of fiction that says what it wants and doesn’t give a damn about commercial rules of order.

10. Back home, the two other books from Antenne look considerably different now. They are both funnier and more pathetic and I can’t help but wish Boullet luck. He exists in a kind of agony of self-awareness, ceaselessly asking, Is that all there is? His generation, ten years on either side, have all gotten the point: one can create safe, “conceptual” or post-Dada work and, on the European model, glide quite smoothly into the academico-gallerist-museum structure where your more or less meaningless work will pad out show after show. You will get residence after residence and live reasonably comfortably. Boullet meanwhile paces the beach like a Scottish Hamlet, has photos taken while he pushes driftwood around in various poses of Artist At Work, and worries the Whole Thing. He is a messy version of this generation’s Duchamp.

11. “Never think of minimizing the importance of challenging accepted truths, and you should go against the flow — you will go where no one else dares to go. You will enter the eternal uncertainty, and you will never come back — but even if you know it’s a road you have to take, and even if you know that road is closed, you should go there — in the dark. Alone. There you will find something real.” So saith the Bear in his broken English.

“We shall not forget that yesterday you glorified each one of our ages. We have faith in the poison. We know how to give our whole life every day. Now is the time of the Assassins.” – Rimbaud, Illuminations.

By Iddhis Bing