The appropriately titled Curtains, Eileen Quinlan’s spare exhibition at Miguel Abreu, unsettles in ways few shows dare. The 24 black-and-white prints, all gelatin silver, communicate a spirit that is both cryptic and choleric. They dampen, these images, as in deaden. They silence. One feels in their presence as if having stepped into the afterings of a wake, casket still open, all guests gone. Something lingers.

Part of what disquiets in this utterly hushed series is the spectering of Quinlan’s aggressive hand, which haunts in ways comparable to the cramping of a limb not long ago severed. It manifests as fitful revenant in openly hostile attacks against the negatives themselves, which are scarred with slashings and steel wool scourings and experimental broodings borne of plain artistic urge. A good dozen-plus prints in the show reflect the latter. As fly to wonton boys, killed solely for the sport, the negatives for these prints were left for hours or days in chemical baths, eroding or outright obliterating any image that might have been and erasing with it any expectation as to what a photograph should even minimally convey. To that end, these prints merely allude to photography, working as they do in the same medium. They are acting, however, in an alternate other: as medium in a kind of necromancy. They conjure rather than represent.

Summoned prominently throughout the series is the artist’s twin sister, who appears in various states of alarm, wistful cheer, or melancholy. In Sister,we find the twin relatively pert, with a ready smile and kitten in hand. But something is off. The kitten has a glaucomic, breathless glare, as if held too tightly in her handler’s grip. The sister, for her part, is not so much showing off the kitten as using it for shield against a lens that seems a shade too intrusive. Its placement, however—the kitten’s—leaves the twin partially defaced and her remaining eye is Cyclopian and slant and communicates a presence only half there. She could be looking at us or through or nowhere at all. The shot’s dis-ease is further amplified by the intervention of the artist herself, the other half, who nearly halves the image again into chemical abstraction, then attacks what’s left with fingernail-like gashes that cut at the kitty’s already traumatized face, around the sister’s nose, across her forehead.

I suspect a conflict. And since this show so ruthlessly prods at the imagination yet so graciously and receptively allows for an imaginative response, I propose an interpretation, however partial, one that’s fraught with sisterly cattiness. Mindful to the show’s title, something indeed feels hanging in the space between picture-taker and subject, a separation of sorts, a curtain. Might it have anything to do with the lounging male friend we see in Tulips? Tulips is one of two prints in the exhibition that is a rephotographing of photograph. In other words, the artist pins a snapshot to a wall and shoots it again in place. The other such print, a virtual twin of the first, is Lady. The single difference being the snapshot in Tulips is swapped out for a snapshot of the sister. As they hang in the gallery, the sister in Lady looks back grimly toward the male friend in Tulips, as if in judgment or in longing. Finally, in Open City, —the last we see of the sister before the series moves entirely into abstraction—the twin looks entirely worn, as if from years of loss. In her hand is a photograph that bears the considerable weight of her gaze. What faintly bleeds through the backside of that photograph appears to show a photo within a photo, as if she too is looking at the same image we look at when viewing “Tulips.” What is the relationship between the sister(s) and this male friend, and is it a corroding source of sibling tension? The remaining abstractions in the series prevent any firm conclusions, which in a way duplicates the interesting and disorienting effects we experience when viewing at least half the images in the collection, i.e. it effectively obliterates our ability to see the whole.

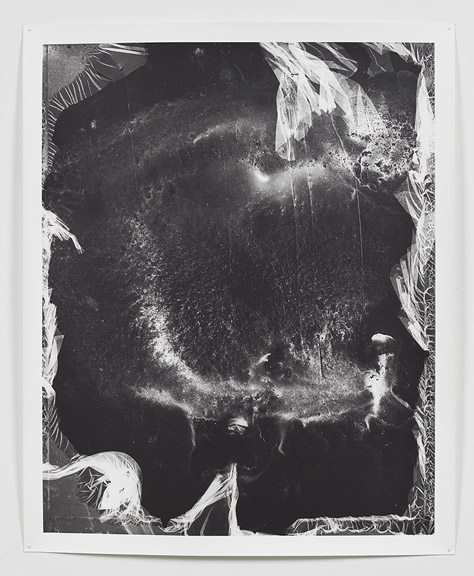

Of these abstractions, one of particular interest, in part because it works nicely as a metaphor for the show, is Sun and Stars. The composition is a record of its own developmental decay, a kind of graphic birthing that comes in allowing the negative to waste away in a corrosive wash. The result here, as if through a chemical big bang, is a spacial, densely celestial realm that orbs and turns and at its outer edges frays. In it a ghostly traveler floats up from the thick, clutching to the tatters of some astral fabric as he attempts an entry into the illumined core. Though not yet through. He remains ever at the edge, in the purgatorial peripheries of a lovely, long-sought world.

A companion print—yet another twin, though this one in way of a polarity—is Top Down. Top Down is a charged, lightning-blast of an image that would be no stranger amongst Dore’s masterful illustrations for Dante’s Divina Commedia; his “Burning Graves—The Heresiarchs” would be its perfect companion. Quinlan’s image would likewise welcome an embedded quote from that same canto Dore so splendidly illuminates: “And now there came over the turbid waves a crash of fearful sound, at which both shores trembled: a sound as of wind, violent from conflicting heats…” Indeed, the image crackles in white hot shards that crystalizes its upper spheres before flaming Phoenix-like into a simmering darkness. Top Down is the burning heart of Curtains, a series that otherwise roils in its own quiet storm.

By Christopher Hassett