He had shown that the image did not exist, only chains of images, and that the very way these were assembled, from the genetic code to the Renault production chain, this assembly itself constituted an image, an image that reflected how we fit into the center or the periphery of the universe.

–Jean-Luc Godard, “Changer d’image”

In a video commissioned for French television in 1982, whose narration is quoted above in translation, Godard wrestles with the question of whether and how images can resist commodification. The exhibition that joins works by Linda Francis, John O’Connor, and Ken Weathersby similarly makes me think about how artists can have a critical relationship to the near-omnipresent forces of the commodity market, in a culture of capital that has expanded even further over the past few decades. The artworks here provoke questions about the flow of capital exchange that seems to saturate every aspect of our lives.

Fluidity, flexibility: oft-cited keywords of the transnational corporate economy, which penetrates public space and institutions through privatization, and personal experience through digital information technology. The mobile realm of production contracts labor wherever profit is greatest, while the deregulated financial industry increasingly speculates on the flow of symbolic capital itself. Smooth operation is ostensibly the order of the day.

Placing high stakes, making hearts ache / He’s loved in seven languages / Diamond nights and ruby lights, high in the sky / Heaven help him, when he falls

–Sade, “Smooth Operator”

Linda Francis’s recent work is based on electron-microscope images of the surface of a failed heat shield of a 1990s space shuttle, images that she overlays repeatedly on the computer. Her pieces present technological visualizations of physical structure—a structure designed, unsuccessfully, to harness resistance. The artworks also incorporate into the imagery evidence of the media that produce them, such as pixelation.

In Interference, the crystalline components arrayed within the image suggest patterned organization while eluding it. Yet across the multiple silkscreened prints assembled in the piece, repetition and alignment at the edges structure the image. Thus pattern recognition in Interference is both fugitive and precise. Indeed a strong diagonal current crosses a literal gap to a separate, larger panel that leans on the floor against the wall. Shifts in scale and near-repetitions are vertiginous.

Also patternlike but dizzyingly evasive, We Can Build You is a more physically factured, painted version of the image at greater magnification. It resembles representations of biological code, and its title (taken from the Phillip K. Dick novel) evokes the manipulations of biotechnology, and more generally the way technological capitalism works on us. Francis’s pieces invite contemplation of hypermediation and replication, as well as contingency, fissure, and friction, with a coolly observant gaze.

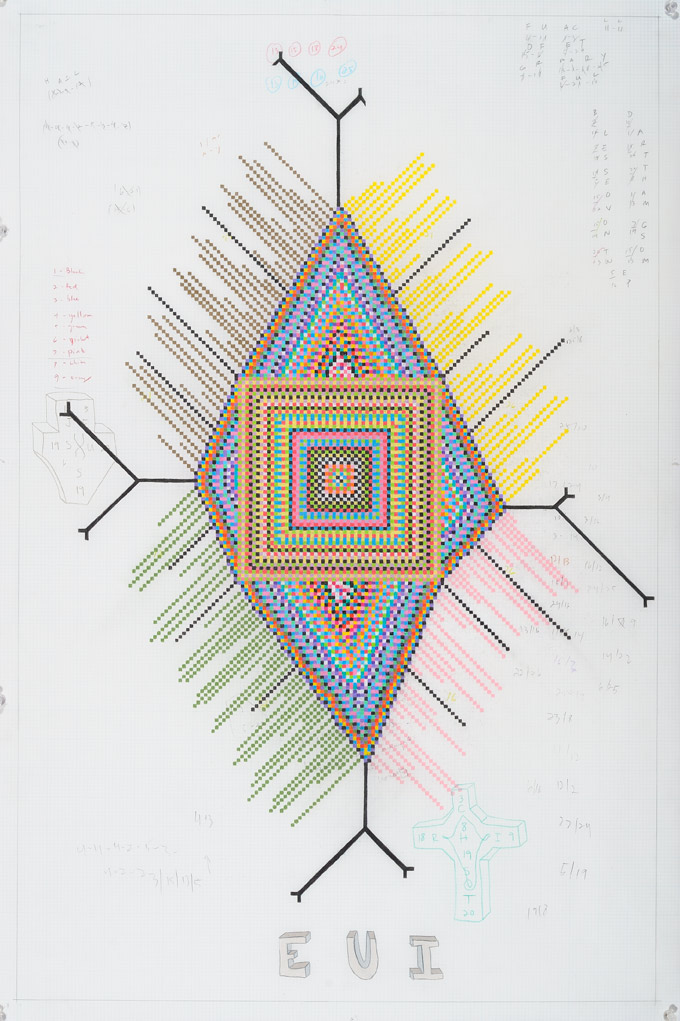

John O’Connor also indexes research material in his drawings, which underscore the imbrication of psychological experience with an information economy. As the Surrealists channeled the illogical logic of the unconscious, O’Connor cultivates delirious overloads of information processing. He produces drawings by using shifting, idiosyncratic codes: converting text into numbers, reversing letters, translating letters into colors by randomly devised systems, running garbled text through an electronic dictionary.

Turing (named for the computer scientist and his famous test of whether machines can think) presents an oval loop of linked bits of textual data. The loop surrounds a set of inwardly folding, bunching shapes that evoke an organism introjecting and expelling. O’Connor generated the incomprehensible data by a dialogue between his free associations, processed through multiple overcodings, and an electronic dictionary’s responses (one of which eerily speaks to Alan Turing’s persecution for his sexuality). Characteristic of the artist’s work, the drawing appears both diagrammatic and indecipherable.

In SUSEJ, a drawing of intricately colored grids, O’Connor includes notations of his text-to-color coding at the paper’s edges. The piece invites us to comprehend the design of the delicate arrangement of colors, but its structuring principles are opaque. Similarly, the thin, almost weightless sculptures Future Rods are covered in blocky text concerning prediction, which resists deciphering. Obtruding on the gallery floor, they evoke the forces of futures speculation that invest contemporary life.

O’Connor’s artistic practice mines the extra-aesthetic, representing processed information from the provinces of socioeconomics, politics, science, mass culture, and personal life. His work does not so much assimilate these realms into absorbable images, but rather creates incongruity, discordance, uncanny disconcertment.

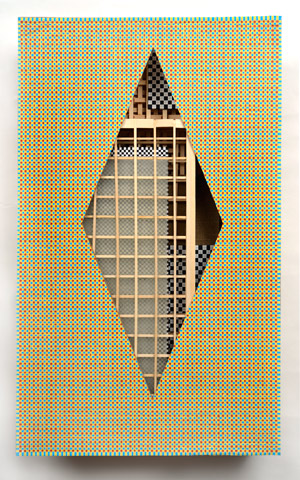

Ken Weathersby, on the other hand, makes dissonant the constitutive elements of conventional art objects themselves, specifically paintings: that is, paint applied for perceptual activity, canvas or linen, and wooden support.

In 198 (dc), paint is applied to a wood support, but that substrate is also image: it’s an elaborate grid of layered wood strips, which cutouts in the painted front surface reveal from the picture plane. Meanwhile the painted image, an optically active grid of black and white squares, is a material slab of acrylic film directly glued to the wood. The resemblance of the grids, and the equivocation of figure and ground at the level of image and physical material, confound distinctions between structure and surface.

In the freestanding 194 (z), another painted grid of tiny squares echoes a larger grid of wood strips that supports the painting. In this piece, the wood strips enclose the painting, holding it within. The structure is a delicate cage that partially obscures the painting, here in its conventional form of acrylic on a rectangle of fabric over stretcher bars. Planar yet viewable in the round, the hybrid 194 (z) presents us with ambiguity about what is supportive structure and what is visual display.

Weathersby’s work foregrounds how the realms of visual image and material production are implicated with each other. It is as though painting is posing questions about its constituent terms. In 197 (dcch), what looks like a painting—a thin plane of an optically active grid of colors—is dissected to present a literal, physical interior that contains overlapping parts of other gridded paintings and wooden grids. The piece highlights a sense of imbrication and conditionality.

Interestingly, the container is also a key figure in contemporary economics; the container ship is pivotal to global exchange, as it’s designed to make the supply chain as smooth as possible. Indeed, as the forces of transnational capitalism are ever more pervasive, they operate largely below the threshold of perceptibility. The artwork of Weathersby, Francis, and O’Connor each raises issues of imbrication, of congruence and incongruity. It resonates keenly with the extra-artistic socioeconomic situation, and its discontents.

by Michele Alpern