Curated by Kasia Redzisz and Lauren Barnes, the exhibition brings together works that share the artist’s particular device of framing his figures. For such a long time we have all focused on Bacon’s preoccupation with the visceral subversion of our physical form, while certainly paying less attention to the artist’s spatial constructs: the world in which his figures reside. This architectural form serves to isolate Bacon’s raw screaming lumps of meat – this we already knew. But the artist’s cages are his recurring ‘leitmotif’ embodying a specific idea: that Bacon’s approach to space was of equal importance to the artist’s approach to the human form. The space frame was the essential context for his existentially wrought bodies.

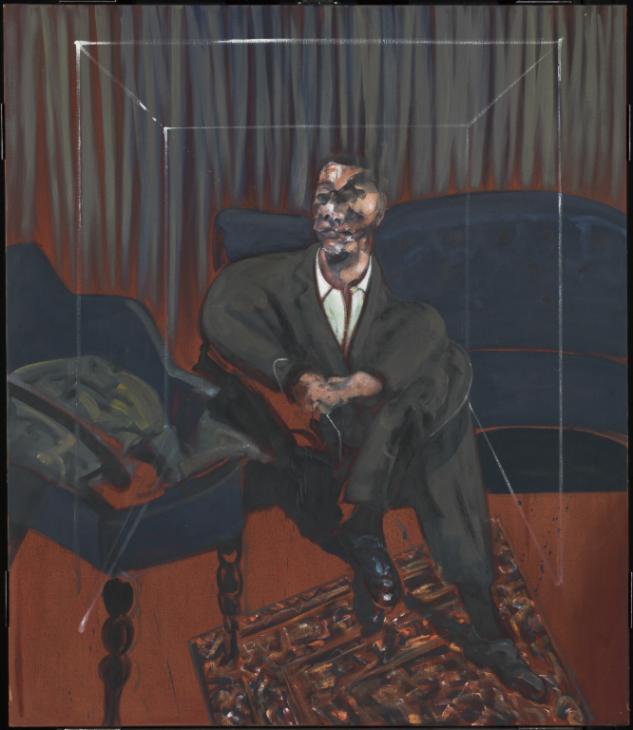

Seated Figure 1961 Francis Bacon 1909-1992 Presented by J. Sainsbury Ltd 1961 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T00459

This is never more apparent than in Bacon’s ‘Man in Blue IV, 1954’ and ‘Man in Blue V, 1954’, displayed midway through the exhibition – devoid of the artist’s later cavorting carcuses – instead the central lone figure of each painting is placed in an abstracted space evocative of a room-like environment through the demarcation of space. The faces of these two figures [The paintings being placed together in situ] are closer to traditional portraiture than in other works by the artist, but with a ghostly transparency. These are reminiscent of many other of Bacon’s works from the 50’s, where there is a subtlety to the figures that would later become unusual: forms slightly closer to traditional figuration which would be discarded in later paintings. This gives rise to an increased focus on the spatial environment of the painting; a mixture of representational and abstract lines. The isolated male figure, possibly Bacon’s lover Peter Lacy – is thought to reference the ongoing illegality of homosexuality during the period – leans trapped in an architectural space: a dark and empty room inundated with a superabundance of claustrophobia and social estrangement. With these works the device of the cage is highlighted, the power of Bacon’s space frames are apparent and create that essential context.

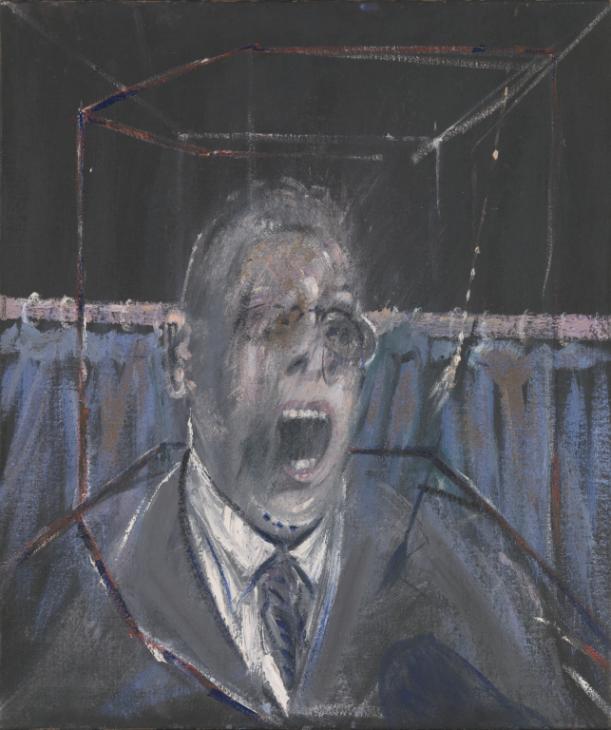

Study for a Portrait 1952 Francis Bacon 1909-1992. Bequeathed by Simon Sainsbury 2006, accessioned 2008 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T12616

It is now no wonder the artist considered creating sculpture (and why Damien Hirst ‘converted’ certain paintings by Bacon into vitrine-enclosed three-dimensional works). Perhaps Bacon could have worked with ‘actual’ space in light of his interior design background, which obviously had a greater influence on his later work than was ever truly realised. As here there is an acute awareness of the spatial properties of the artist’s compositions. Bacon understood and manipulated the architectural space of his paintings to effect his figures. While our eyes were all focused on twisted meat and screaming nurses, Bacon was manipulating their place in the psychological halls of our minds, adding pathos and isolation to the violence of the flesh.

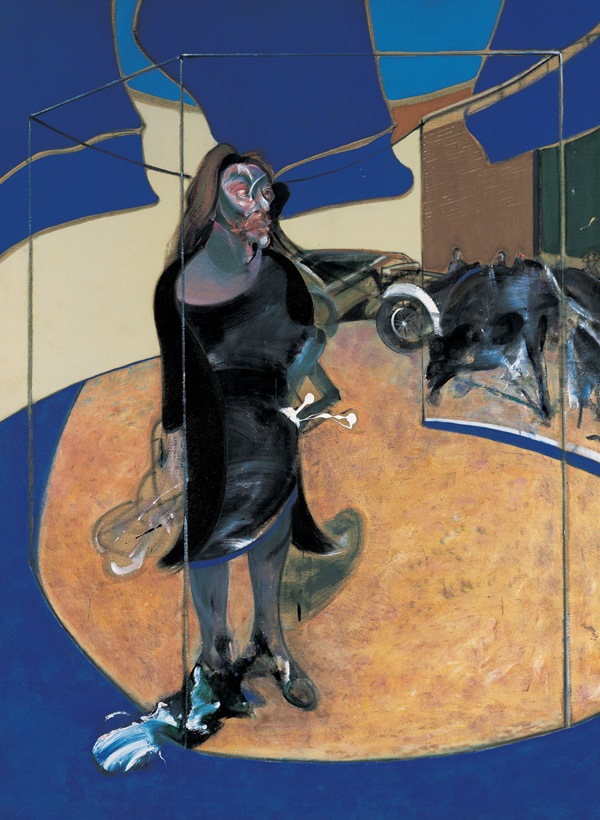

These space frames of late 50s have a greater complexity in later works as the ongoing motif evolves. With ‘Three Figures and Portrait, 1975’ elliptical and circular ‘lenses’ focus on the corrupt body of a suicidal George Dyer with a sense of sadomasochistic voyeurism. These architectural devices not only focus our attention, but also the intent of the artist’s vision, in this particular work the device is a reflection of the artist’s own history with the subject. When British art critic and curator David Sylvester asked Bacon about the artist’s cages and space frames, Bacon replied: “I cut down the scale of the canvas by drawing in these rectangles which concentrate the image down. They are there to highlight, to focus, to point to the figure. They are intensifiers.”

Francis Bacon, 1909–1992 Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho 1967 Oil paint on canvas 1980 x 1475 mm © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2016. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Acquired by the state of Berlin

These cubic cages give a solitary existential angst to the artist’s contorted flesh, as behind the visceral screams simmers a neurosis. The rawness of ‘being’ belies paranoia, angst, loneliness and loss. A theatrical stage for the artist’s writhing spines and tortured faces: there is nothing beyond those walls. Nothing beyond the frame. Cages, chambers, and fenced frames lock Bacon’s subjects into a temporal Godless eternity. The flesh rendered all the more futile because of its architectural prison.

The curatorial decisions made in this exhibition highlight the artist’s Godless architecture. It is apparent that Bacon’s ‘theatre’ was of the same importance as the artist’s ‘players’. With all of the myth surrounding Bacon as an instinctive painter, immediate and visceral – from the existential angst of the 50’s to what is sometimes described as almost the self-parody of the artist’s final works – Bacon maintained the physiological complexity and considered structure of his spaces. The real existential horror of the artist’s environments was never really to be found in Bacon’s renditions of screaming haunted meat, but in the voids surrounding them.

By Paul Black

NY Arts

Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms – Tate Liverpool, UK – until 18 September 2016