By Xiaoyun Helen Zhang

Art is only one of the multiple venerated idols in the grand Temple of Human Minds. We concern the power of art transcending borders of vital importance to the Ultimate Question: Can people understand art between cultures, over diversified barriers of faith, aesthetics, wealth and ideology? To be more precise, how could an ordinary American, born and live in a free and developed country, really understand the ideas of a contemporary Chinese artist who breathe post-totalitarian air and witnessed a fast social progress never seen in human history?

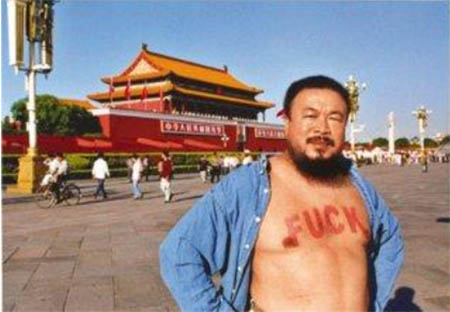

Some would say “Yes!” and put Ai Weiwei up on the table. Why was it that Ai’s artistic creations were widely accepted in the Western Hemisphere while other Chinese artists struggled for entrance into international views? The answer was seemingly quite obvious: Ai Weiwei deals with international themes using international forms. The forms he adopted and themes he discussed are both easy-to-get: he employed performance, sculpture, among other popular expressive methods to deal with the universal theme of “oppression and anti-oppression”. In short, his creative fight is a common struggle, which just happened to happen in a Chinese context.

My experience of starting with familiar themes happened in our first show SINAMERICA I, back in 2015, which attempted to introduce emerging Chinese Artists living in New York to U.S Audience. The enthusiasm of being noticed was high among this community consisting more than 300 young talents. We spend extra time to go through a huge number of submitted works before deciding which to be put on stage. The standard I had in mind was simple and clear: we must start with something that international viewers would love to see most. So Jin Yu’s fantastic fake monitors were presented on the final version of the show. The talented young Chinese female artist’s devices were placed on hidden-yet-still-obvious places around the gallery (especially including lady’s restroom) to remind people of the existence of a technocratic post-totalitarian surveillance, in a relatively nifty tune. This on-site sculpture art piece can be seen as a cute echo of Ai Weiwei’s white marble camera. This kind of art is naturally universal, speaking both mean and end. Jin Yu’s work of less seriousness and equal meaningfulness won quick comprehension among the general audience at the opening night.

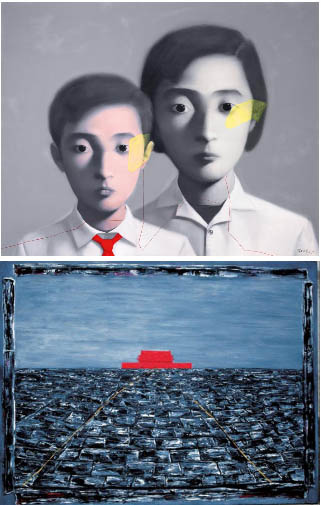

Skipping the Ai Weiwei style, more sophisticated and yet equally successful artists such as Zhang Xiaogang could present his opinions and feelings on China’s mix of pre-modernity and post-modernity in a more delicate way, which requires slightly more effort to be understood. Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline-Family series are, as critics described, about Chinese Face, Chinese Family and Chinese History during the last 70 years. Yet the themes Zhang Xiaogang treated could still generate enough universal consonance among the generation of the Cold War. Bloodline-Family series still very much concentrated on the personal experience in an oppressed society. His Tian’anmen series, however, are of less subtlety (though still much more delicate than Ai Weiwei’s treatment on the subject), which satiric nature requires minimum effort in interpretation.

Zhang Xiaogang’s subtle yet still obvious references

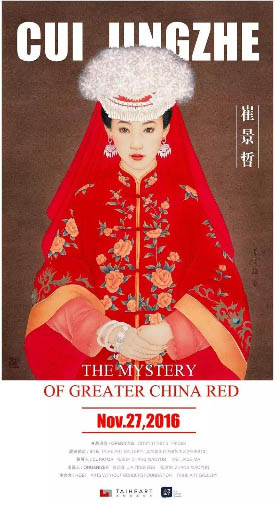

Arts like this are easy to read, or say, naturally universal, especially when the theme and figure presented are concrete and stereotypical: landmarks, facial expressions, or simply pretty girls (laugh). All you need is to present it and let the Wow begin. In our most recent exhibition, the Mystery of Greater China Red, I introduced Cui Jinzhe’s resurrection of China’s classic lady painting. His works already have an established status in international market, especially Russia and Middle-East. His forwarding artistic intention has won him universal appreciation, by putting attractive Far-East femininity in iconic Chinese red bridals. And that’s all you need for introducing further the heritage skill of Gongbi he applied on these vivid eye candies, a fine brushwork style in Chinese Water-and-Ink painting, which requires unspeakable efforts on meticulous details.

Things can be bit more complicated when it comes to less universal art skills presenting less universal themes, especially when Traditions became a more important player among all. It is almost impossible for young people of the West to widely appreciate manuscript drawings from Medieval Europe; how would you even expect to directly introduce Classical Chinese Art, which came down from the same time period, into their modern consumerist minds? In comparison to Ai Weiwei and Zhang Xiaogang, who both fall in the category of Contemporary Art, how could we make more peaceful and inward artworks of long inheritance? Such are the challenges facing international curators, whose re-interpretation process could be just as important as the original works. So, to my fellow curators and curators-to-be, I intend to list some helpful tips. So read carefully:

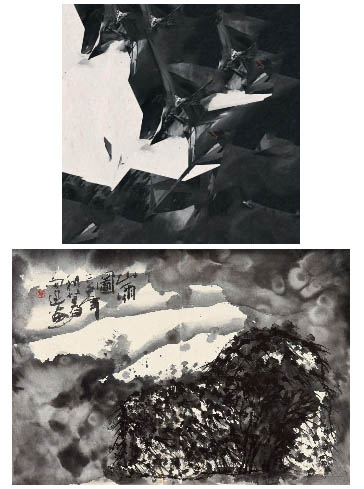

A recent exemplary re-interpretation of mine would be: How to introduce Shanshui (Mountain-and-Water painting), a historic category of Chinese Art, to the general public in New York? Traditional Shanshui could prove difficult at keeping Viewer’s Attention for more than 5 seconds (the necessary human gazing time before fall in love with each other), so we the Art without Borders started by presenting a modern metamorphosis of it first, as the young second-generation artist Chen Baoyang digitalized his father’s famous Shanshui masterpieces and printed the recalculated version of them on 4×4 inch canvas, creating a rather eye-candy like attraction to mediocre eyes. Hence his father, Chen Xiangxun’s traditional works were better noticed as viewers approach to savor the difference. This present-past bridging attempt was done in our recent exhibition of X-ATRAMENTVM II, which achieved great acceptance among viewers from different culture backgrounds.

Chen Baoyang’s digital reprint is the doorway into his father’s artistic legacy

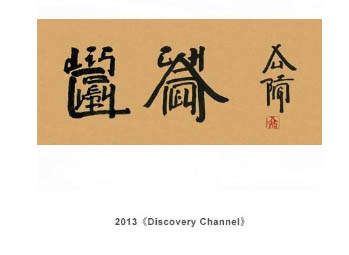

Chen Baoyang’s creative methods were much like Xu Bing’s. Xu Bing’s signature, the retro-engineering of Chinese hieroglyphs mixed with Latin Letters, took the art of Chinese Calligraphy to a whole new level. As traditional Mountain-and-Water images were revived by state-of-the-art programming, Xu Bing reorganized English letters and words into traditional Chinese characters. Hence similarly, referencing Xu Bing’s imaginative characters could be an effective way to generate substantial interest while introducing the much more traditional art of calligraphy.

Another exampling work done by Arts without Borders is in our Chinese Renaissance Series. While representing older forms of traditional painting skills, we intentionally selected Duan Gexin’s water-and-ink cartoon to introduce younger international crowd into appreciating the ancient skills of water-and-ink. The methodology is obvious: aim for recent contents done by good old skills. So here comes the first tip of transnational exchange in art: choose a bridging device between here and there, that is, to use intermediary art works when crossing culture barriers of Time.

Artist Duan Gexin, using traditional skills on cute comic figures

However, when without the kind support of these culture hybrids as reference, some ancient artistic concepts could be confounding: such as the Jinling School, a major painting style discovered by a group of artists living in the city of Nanjing back in 17th Century. Art History is already a boring selective because of too many types, genres and methods, so why bother introducing them like a babbling professor? Here is the thought I had when I decided to name the serial shows presenting new masters of this prominent category using Latin, as the SCHOLA NANKINENSIS. Who understands it? No one, yet it draws much more attention than simply going with long subheading of “introductory expo about an important Chinese Traditional Art Genre”. SCHOLA NANKINENSIS. Yes, as if you were discovering the art as Matteo Ricci, 17th century missionary to China, a rather proper perspective I want for my western viewers to impersonate. Similar efforts were done in order to ensure consistency in Time and Ideas, while translating other terms implying ancient arts in our serial shows. So here is the second tip, when dealing with major leaps in Time with no good bridging artworks at hand, try to pair a sense of contemporariness in your translation efforts.

A third tip I want to share with you is not a trick, but a feeling. As we were doing Shi-Cha, an opposite show of SINAMERICA I (Chinese Emerging Artists living in New York) dealing with Western Emerging Artists living in Beijing, I discover that the most cross-culture communicable experience comes from these young motivators of art, as they transform ordinary touches into inventive expressions. They actually share feelings of surprising similarity: foreignness because of distance and inadvertently a strong desire for homogeneity: A Chinese girl employed bed sheets as substitute for rice paper to write down her wildest dreams in calligraphy while a British painted his figurative diary on Chinese flowery table clothes. These are spontaneous artworks which provided a quasi-anthropological way of introspections. As we are relocated on Time Zones, we are also departed from our Culture Safe Zones. The only things we hang onto by instinct are the ordinary pieces in everyone’s life and ordinary emotions sharable by all. In a sense, common and basic feelings are the last and most important method all curators should be counting onto facing multicultural viewers: love, sadness, fantasies and a sense of loss.

Xiaoyun Helen Zhang, curator on site