Our times are the times of materialistic values, of greed, of self-indulgence.

Herod is dancing in Chambliss Giobbi’s Tanz für mich, Salome!, inspired by Richard Strauss’ very modern opera based on the Oscar Wilde play Salome. Giobbi loved the music but has turned the story around and made Herod the one dancing. This collage is filled with the image of an aging, overweight, almost naked man full of faults. He is incestuous, adulterous, and on his way to seduce his stepdaughter. For this image Giobbi used his own body as a model—a brave thing to do, since Herod is anything but handsome.

Herod is dancing. His expensive robe is open, showing most of his naked body. His head, arms, and legs all have multiple images, as Giobbi uses this “cubistic” method to capture movement. The two heads betray Herod’s indulgence with food and wine. In Wilde’s play Herod invites Salome to “Dip into it thy little red lips, that I may drain the cup” and, “bite but a little of this fruit, that I may have what is left” but Salome refuses. Herod still drinks the wine and eats everything else too. In Giobbi’s image we see the remains of red wine and food all over his face. He’s reached a point of drunkenness when reason is no longer bothering him. He touches his right head in a moment of recognition of his madness but he can’t stop dancing just now. Jewels cover his body. All of his fingers are richly ringed. One of his fingernails is badly bitten. He has worries. Metal necklaces surround his body like snakes.

Giobbi was a composer of classical music before he turned to visual arts. As he said, in music “time contains every move we make, everything exists in time, develops over time. I love the idea behind cubism. I love the brutality of it, the honest kind of brutality of it. These are like getting multiple moments of time; doing the direct opposite of (music), like compressing multiple moments in one cathartic image.” In the way that music is composed of single notes, Giobbi’s collages are created from thousands of little pieces. He takes portraits of his models, sometimes as many as 300 images, from different perspectives, enlarges them on the computer (but doesn’t modify them) prints them, and then cuts them into small pieces in order to create his compositions. He uses boards as a base and covers the finished work with a thin layer of beeswax to keep the pieces in place and so they will also “smell good.”

However fascinating his method is, Giobbi’s main focus is the character of his models, “I look for people with a free spirit and strong character; who stand for what they do with great conviction and passion.” This search often leads him to well-known personalities such as artists Joe Barnes and Alice O’Malley, filmmaker Fisher Stevens, performance artist Penny Arcade, or cult figures such as Indian Larry, the Chopper Shaman, or the transgender Amanda Lepore. Modeling for Giobbi is a commitment, since it takes about a year until he reaches the point that he knows them really well and feels that he can get into their skin, or more likely under their skin. That’s when he finally gets to the actual work. When there’s no secret left, he recreates the person in his work not as an idealized version but the “full truth.”

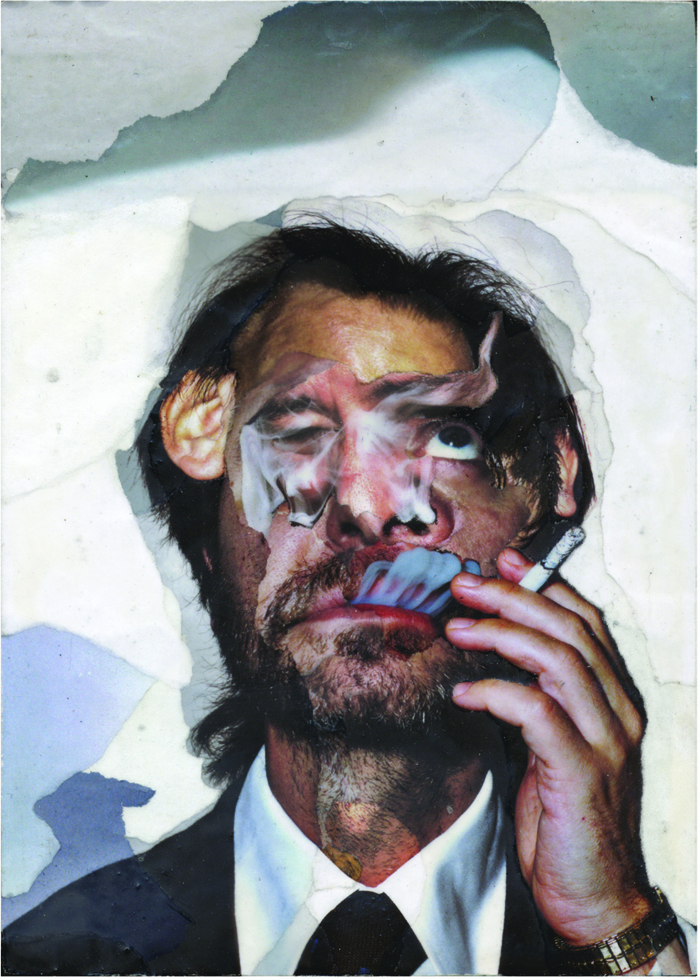

At first sight, you can see that Fisher Stevens is a nice guy, someone you would love to have a drink with. He seems to be a big dreamer whose head is in the clouds, surrounded by the artistic haze of cigarette smoke, while he tells sophisticated and funny stories about the characters he brings into life in his films. Stevens is an accomplished film persona with many movies to his credit including Short Circuit, Hackers, his documentary The Cove and his debut as the director of Stand Up Guys. When he talks about his work his favourite words are, “it was so much fun” or an “amazing experience.” Giobbi got him absolutely right: a nice, amazing, funny person.

Herod is not the only one who is dancing in Giobbi’s compositions. The photographer, Alice O’Malley chooses her models from New York’s club culture, and always strips them down in order to recreate them in blinding whiteness. Inspired by this method Giobbi stripped down O’Malley as she dances in the collages depicting her. There is a lot of stripping down and nakedness in Giobbi’s works. His images of the seven deadly sins (Se7n) are embodiments of unfortunate passions that are pregnant with many evils. They show the aesthetics of the morbid, its cruelty and its beauty. In the collage Pride transgender celebrity Amanda Lepore is dancing in front of a mirror. In their need for exposure Giobbi’s models become overexposed and sometimes too naked, making the viewers into voyeurs.

Herod is still dancing in his Dionysian haze. Does he really dance for Salome? I don’t think so. His dance is no longer filled with desire but becomes a bottomless pit of lust, a burning itch, more like a disease than a pleasure. It is greed that moves him, wanting more and more, never to be satisfied. This modern version of Herod is being consumed by his own needs. Giobbi’s characters are unmasked guests at the masquerade of our times, and his Herod, this overfed, oversexed antihero, leads this mad cavalcade.

By Emese Krunák-Hajagos